Core Modernization 2024: The Next-Generation Opportunity

Sponsored by

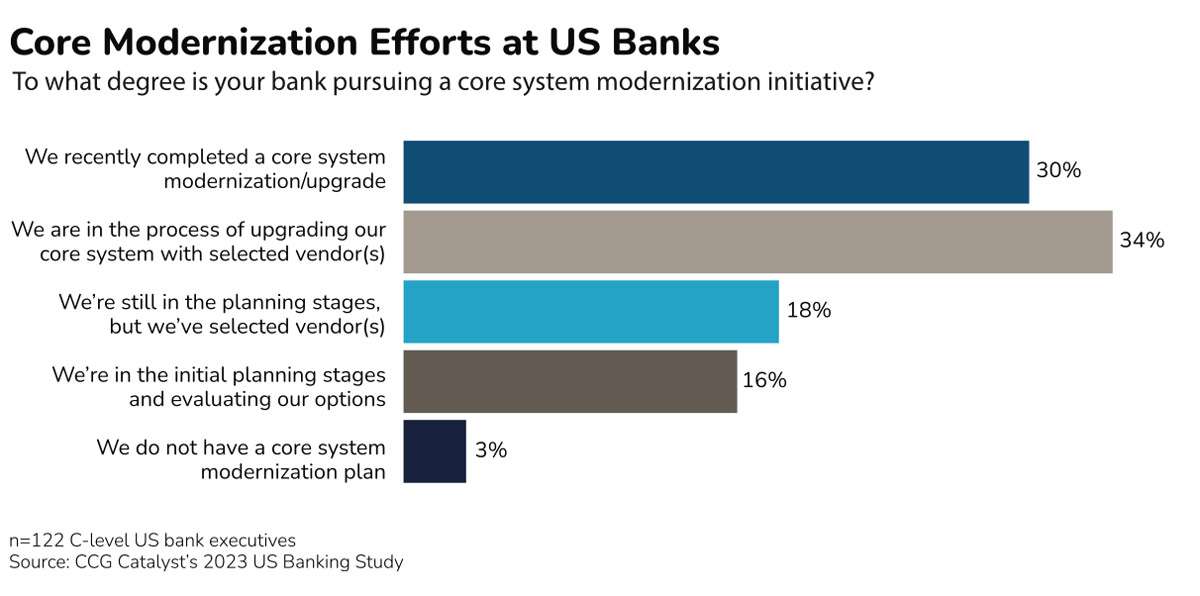

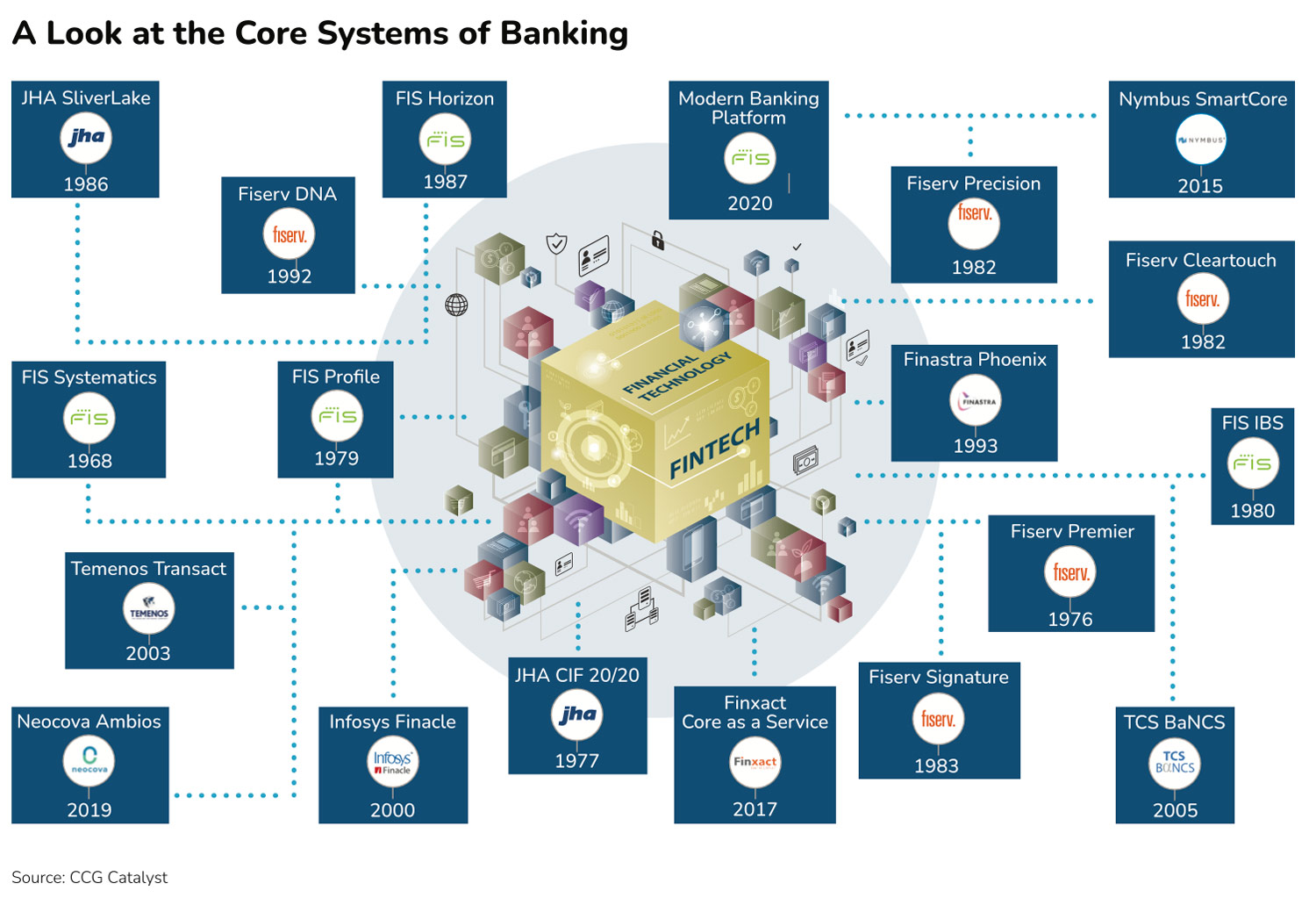

By this point, it is generally understood in the banking industry that legacy core systems are holding FIs back from competing in a technology-driven future. As a result, banks far and wide are pursuing core modernization initiatives. In fact, 30% of respondents to CCG Catalyst’s US Banking Study in 2023 said they’d recently completed a core system modernization/upgrade, while another 34% said they were in the process of upgrading. Just 3% said their institutions have no plans to make changes to their core systems at all. However, those who said they had recently completed an upgrade in large part represented large FIs; only about half of these respondents come from a bank with less than $10 billion in assets, and 14% have over $100 billion. Moreover, traditional vendors still hold a majority of the market in the US, suggesting few are switching to newer options.1

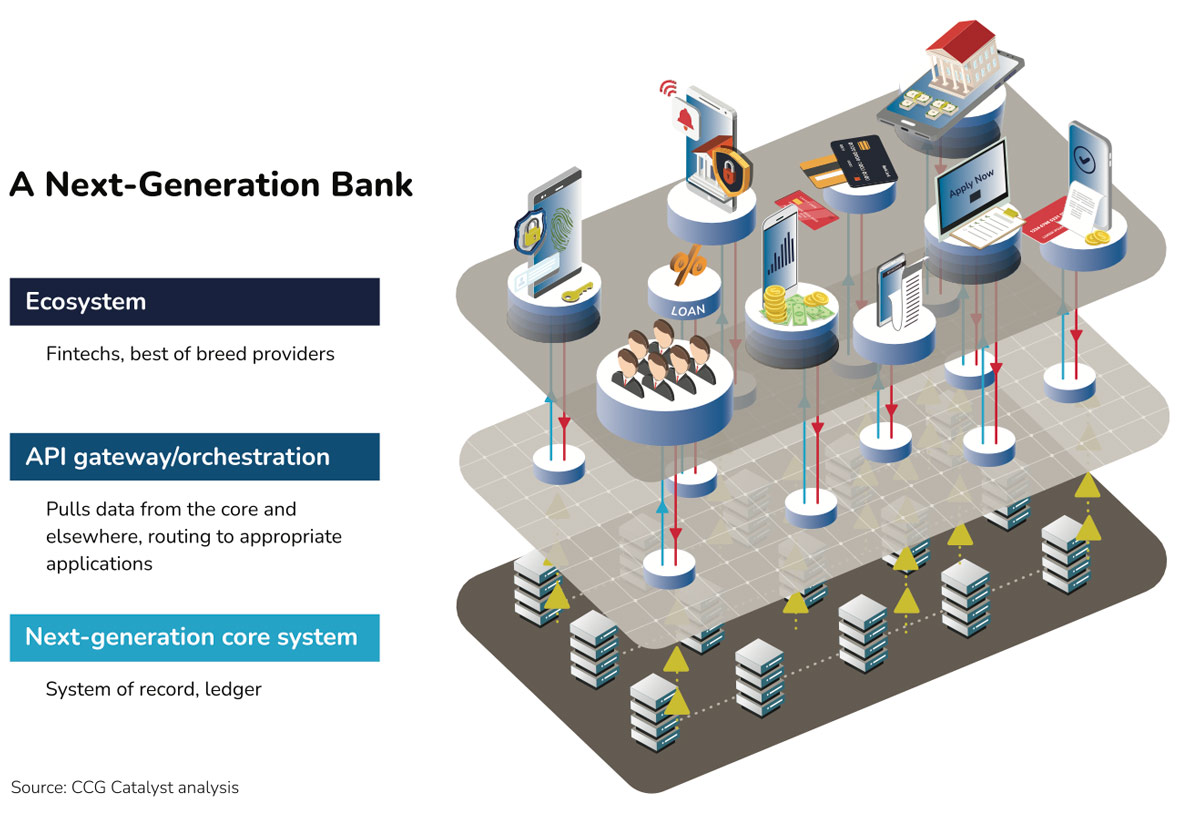

As it becomes increasingly important to make use of innovative solutions in banking, modernizing underlying infrastructure will only grow more critical — for everyone. This is especially true as more FIs pursue best of breed strategies,2 by which they shop around for the most suitable solutions for specific functions, rather than getting everything from a single vendor, a strategy generally termed best of suite. To support this shift, though, banks will need to take a modern approach to modernization. And that will require at least contemplating a future beyond tried and true options, one powered by next-generation technology that can support new and differentiated needs.

Based on our research, core modernization itself is evolving. In this report, we examine what that means, with an emphasis on the emergent technologies and capabilities set to drive the future. The goal is to help FIs understand what embracing next-generation infrastructure looks like, regardless of where they are on their own journey.

Laying the foundation

Most FIs still operate under a services mentality, and while they may intend to adopt a best of breed approach, they simultaneously want their core system to be well established and their provider to be a key partner in those decisions. This is do-able to some degree, but it means the institution is bound by the technical capabilities and limitations of a core system that may be decades old, even if it’s new to the bank. As such, it is important to ensure the system selected can support the bank’s strategy.

Forward-thinking FIs, on the other hand, are leading the charge and experimenting with next-generation infrastructure that offers less support and involvement from the provider but more freedom to act with agility and build competitive offerings. The way these FIs approach modernization suggests where the market is headed long term, both from a capability and migration path standpoint.

According to Christopher McClinton, chief marketing officer at Finxact, three characteristics are table stakes for a next-generation core:

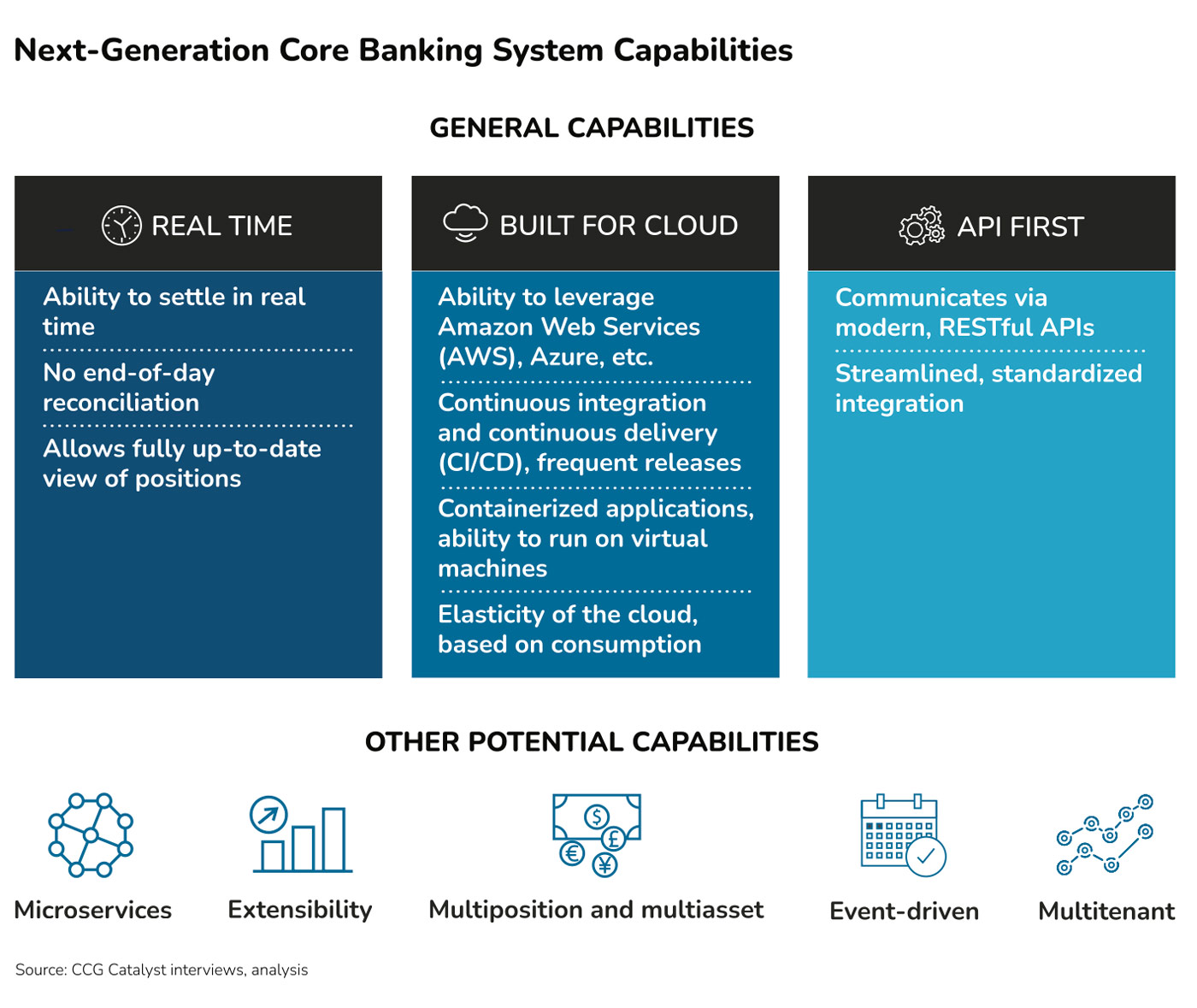

- It operates in real time, with no end-of-day reconciliation.

- It is built for the cloud, allowing for frequent releases through continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD).

- It communicates via modern, RESTful application programming interfaces (APIs).

This kind of technology generally falls into two buckets: core systems from established providers that are revamped for the future and natively built next-generation cores, which generally (though not always3) come from newer entrants. Natively built next-generation core technology tends to push the boundaries further, often acting only as the system of record and providing a “choose your own adventure” value proposition suitable for only the most progressive institutions. Examples of these include Finxact as well as international players like 10x Technologies and Thought Machine.

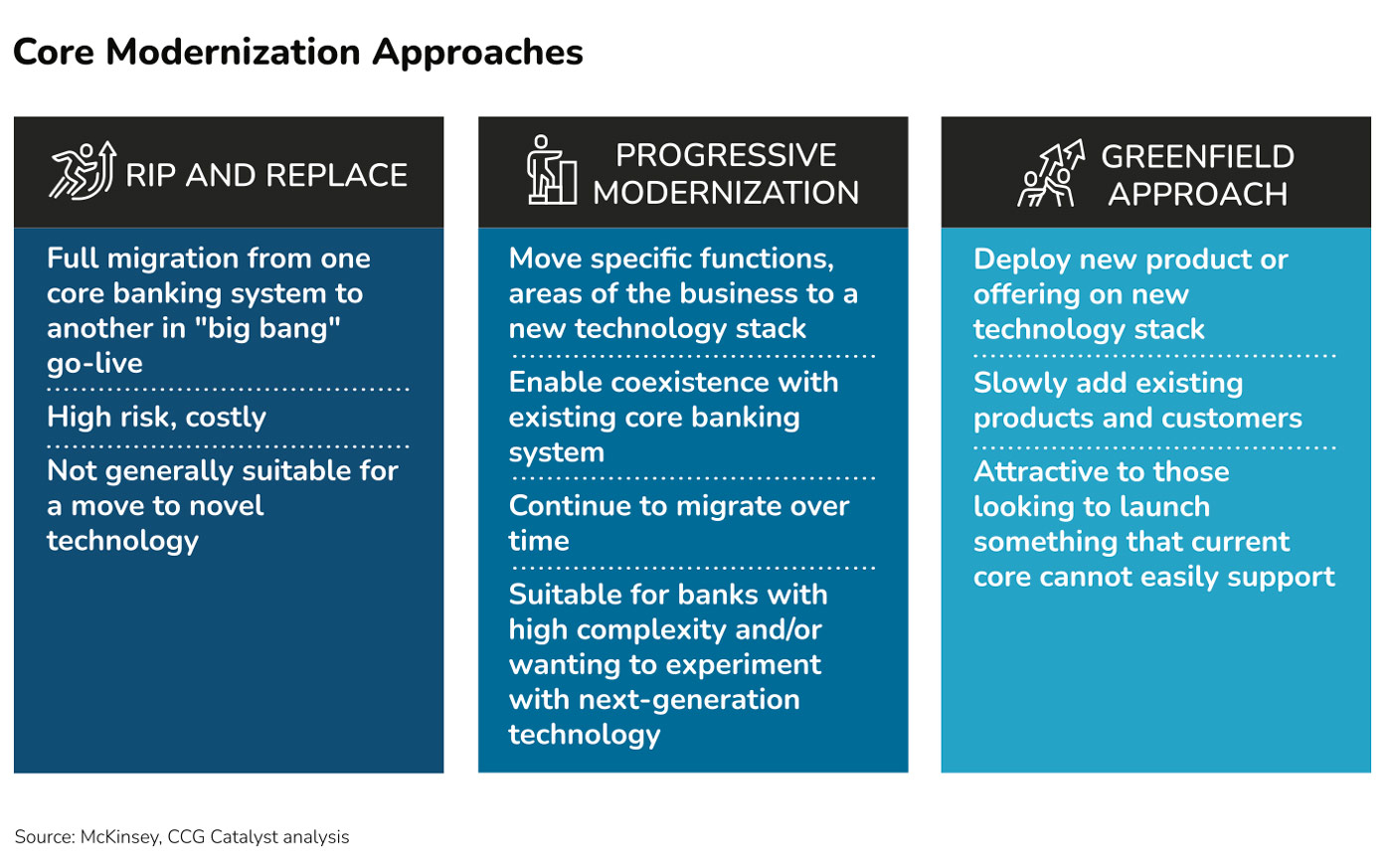

Next-generation technology is extremely flexible; it also is largely unproven. FIs thus need to be able to prove it out slowly. As a result, rip and replace journeys, by which a bank changes cores in one fell swoop, potentially in a single go-live weekend, aren’t attractive. “It’s often far too complex and far too risky to do a rip and replace,” explained Kristiane Koontz, director of banking transformation at Zions Bank, which is currently in the process of a multiyear core transformation effort to TCS BaNCS. “If your complexity is low, and you are going to a tried and true solution, it’s fine. But if you have more complexity or if your solution is novel in any way, it’s a lot harder.”

As a result, we are seeing a number of options emerge for core modernization beyond the traditional rip and replace that can help institutions of all sizes get to the future. These include well-known paths4 like progressive modernization or taking a greenfield approach. What these paths have in common is they are incremental. They are designed to enable banks to get to a new core, safely, while allowing them to explore more novel technology in the process. With any of these approaches, the key is to have a plan that segments the overall project in a way that makes sense for the organization.

In a progressive modernization, there are a few ways this segmentation can manifest. For example, you can break it out by asset class or by geography or by customer segment. The goal is to make the process more manageable, strategically. Zions’ approach was to break it out by asset class, starting with less complexity and moving up. The bank began with consumer loans, followed by commercial loans and construction loans. Deposits were last and further broken out by affiliate — the entire migration will be a decade or so long effort. The results so far, according to Koontz, have included an expected 25% increase in how fast it can integrate new technologies as well as improved data to streamline automation across the bank.

With a greenfield, you’re starting with an entirely new product or customer segment. For instance, a bank may want to launch a high-yield savings account or target a specific demographic like Gen Z. In this approach, the bank would launch the new product on a new core, and then slowly migrate other products and customers over.

In any case, the common thread is that a new core is slowly coming online in a phased capacity, while the old core is slowly being retired. This requires the two to coexist in a seamless way, generally via a coexistence layer5 that is managed by the bank. Over time, the old core loses more functionality, until it operates in a limited capacity or is taken offline entirely, leaving the FI with a modern engine on which to build. (Note: A phased migration could realistically be applied to any modernization effort; it is most commonly associated with transitions to next-generation systems due to their aforementioned complexity and risk considerations.)

Enabling the art of the possible

Transitions to next-generation systems are likely to grow more popular as progressive FIs prove out the technology, reducing the risks associated and making their peers more comfortable. In particular, we can expect to see greater adoption of these systems from established core system providers, especially as they continue to advance their technology and capabilities. As that happens, phased migration paths will probably become the norm for all but the most traditional institutions.

However, the puck is already sliding ahead — as mentioned, a couple of providers with natively built core systems are pushing beyond those table stakes characteristics for a next-generation system and providing a glimpse of what the future could look like on a longer time horizon. While there are a host of possibilities in this new world, two critical considerations stand out, one technical and the other strategic: the ability to leverage microservices and the rise of the ecosystem model, enabling true “best of breed.”

Leveraging microservices

Today’s next-generation systems are generally API first, meaning all of the endpoints are exposed through APIs so the core can consume and distribute information to other systems, and those APIs are built based on modern standards that make integration easy. A stride beyond that is leveraging a core that is based on microservices. According to McClinton, this refers to an API architecture design that allows you to pick and choose different elements. Essentially, he said, the core is built around many small, decoupled services that do specific things.

Such functionality can help make complex tasks simpler, like embedded finance use cases that call for only certain components — for example, a fintech company may not be trying to run a whole bank but wants the ability to embed a few banking products into its app. By leveraging microservices, it can do things like offer a deposit account with a handsome interest rate or short-term loan using only four or five APIs, per McClinton. Some additional benefits include: the ability to scale individually without impacting other components at the bank; the ability to make updates without impacting other components at the bank; and a lack of collateral damage if a microservice were to malfunction (due to its independent nature).6

We’re slowly creeping toward greater adoption of microservices in core banking, but it will take time to get there. There are still few providers in the market that build with this kind of architectural design, likely due to the advanced engineering capabilities required. Additionally, understanding how to use microservices to solve problems and improve efficiency requires commitment from the bank as well as creativity. Over time, though, as such technology reaches the mainstream, it should help FIs significantly reduce their costs and increase speed to market for new offerings.

Ecosystem development

As discussed above, the newest systems often act only as a record-keeper, without all of the ancillary services many FIs are used to. That means that a bank leveraging such technology has both the advantage and disadvantage of choosing its own adventure, and a big part of that is determining who the best of breed solutions in the market are.

As Mark Moroz, EVP, head of deposits and payments at Live Oak Bank, put it, “You have a core processor that is going to be cloud native and API first — that’s great. But you have to build an ecosystem around it. You have to find likeminded companies to attach to that core.” Ask yourself, he said, “Who are the right partners to consume and integrate to those APIs? Think about statements, remote deposit capture, your front end, customer relationship management, etc.”

Live Oak Bank, which is a client of Finxact, has been on this journey since leading up to 2021 when it successfully converted deposit customers to the cloud-based core. The process began by migrating consumer savings and certificates of deposit (CDs), then business savings and CDs. Live Oak is currently building out business checking accounts and will start on loans after that. All brand new products go on the new core. The bank has 15 partners in addition to Finxact, and it has selected each one. Moroz estimates that its approach may save the bank somewhere around 45-50% on its savings product and 25-30% on the transactions side, versus trying to execute the same strategy with its legacy system.

Essentially, what FIs like Live Oak have to create is an ecosystem framework — the ability to effectively assess and onboard different solutions that not only complement the bank but also complement each other. This requires deep knowledge of the fintech sector as well as real vision among executives. With a traditional core system, all of the ancillary services to run a bank are available. But, in a best of breed approach on a native next-generation platform, it is generally up to the bank to design the stack.

Importantly, the system should allow for quick pivots; Live Oak, for example, can easily snap solutions in and out if they don’t work well. In fact, it started off with one provider for remote deposit capture but didn’t like the experience, so it took the solution off the platform and put in a new player. It took 60 days to make the switch, while a traditional core platform might take 9 months to a year including contract negotiations, Moroz said.

At this point, we are looking quite far into the distance in the interest of foresight; not many banks are positioned to take such an approach today. However, it is important to understand the implications of what’s being introduced to the market and how it is being utilized. Additionally, there are options for FIs that want to experiment with the newest of the new in a controlled way that doesn’t fully abandon the services mentality — Finxact, for instance, is owned by Fiserv and can bring its suite of services to the table.

Deploying new capabilities

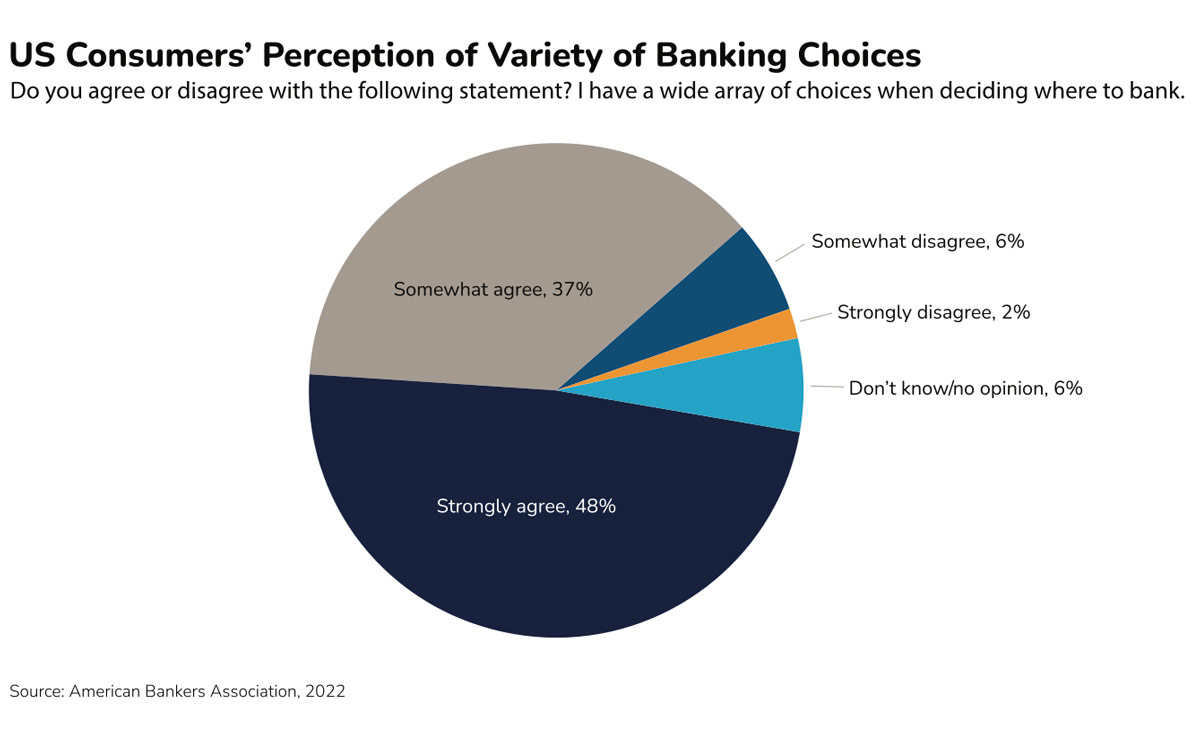

In the end, the purpose of all of this work is differentiation. In an environment where banks need to attract deposits and serve customers profitably against heavy competition, getting everything from a single source isn’t sufficient for many. That approach leads to offering what everyone else has. And, if all of the options are similar, how is a customer supposed to choose? As a result, institutions are being driven to think outside the box to attract and retain customers in a more bespoke way.

The way institutions approach that goal will be different, and as a result, their technology strategies will be different. One constant, however, is the need to create flexibility. That flexibility exists on a spectrum that goes from working closely with your provider to enable new capabilities to building your own ecosystem, with many, many options in between. Next-generation infrastructure (and how it is evolving) represents where the industry overall is headed on that spectrum in the near and long term.

Overall, the ability to integrate with top of the line solutions and deploy updates to products and services quickly are good baseline capabilities to shoot for. But that’s not where the work stops. FIs then need to figure out how they are going to deploy those capabilities. Chances are their modernization journey started with a specific problem or set of problems — more likely than not, the bank wanted to do things its current core provider said cost too much, would take too long, or it couldn’t handle. But in solving for those issues, the bank embarked on a process that offers additional opportunities.

How to capitalize on that will be very specific to each FI. It could be launching7 new products to new demographics; it could be entering8 the embedded finance arena; it could even be experimenting with offering9 access to tools outside of financial services like accounting. The important thing is to always tie those decisions back to strategy; flexibility shouldn’t turn into shiny object syndrome. As Ahon Sarkar, general manager of the Helix core platform at Q2, put it, “You’ve got to know what you’re solving for, and whose problems you are solving for.” What modernization does is provide the confidence that you’ll be able to support what you determine is right.

Sponsored by

Special thanks to our sponsors — we are delighted to acknowledge the generous support of those who made this research report possible.

©CCG Catalyst 2025 – All Rights Reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Download a PDF of this article