US Open Banking 2024

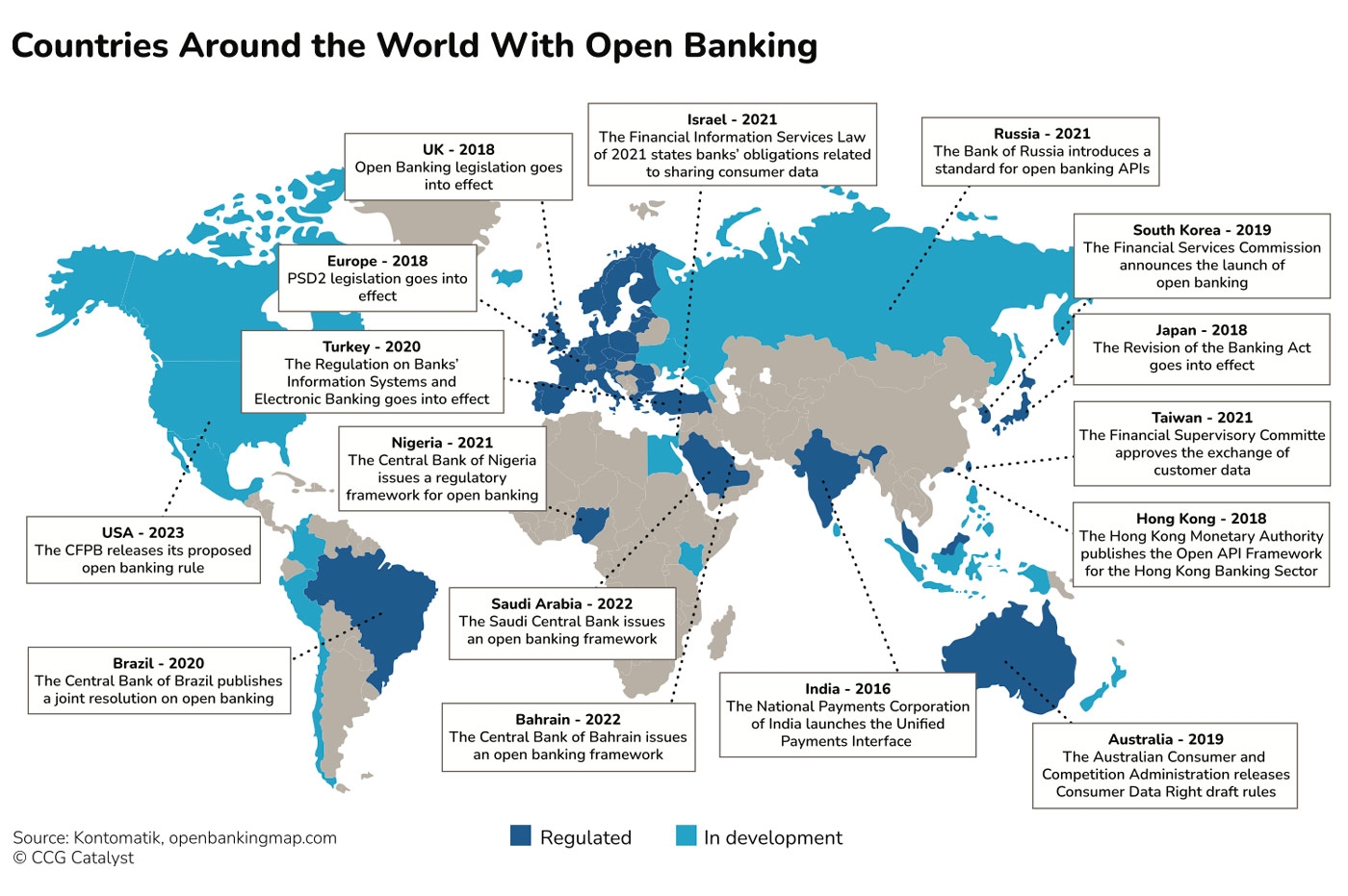

US open banking had a watershed moment in 2023: The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) released its long-awaited proposed rule based on the personal financial data right enshrined into law by the Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank).1 As such, the country is now one step closer to developing a true open banking framework as in other jurisdictions like the UK and Europe.2 Like these other frameworks, the proposed rule would require financial institutions (FIs) to securely share certain financial data with third parties at their customers’ request. (Data covered includes information associated with credit cards under Regulation Z and checking and savings accounts, prepaid cards, and digital wallets under Regulation E.)34 It is expected to be finalized this year.

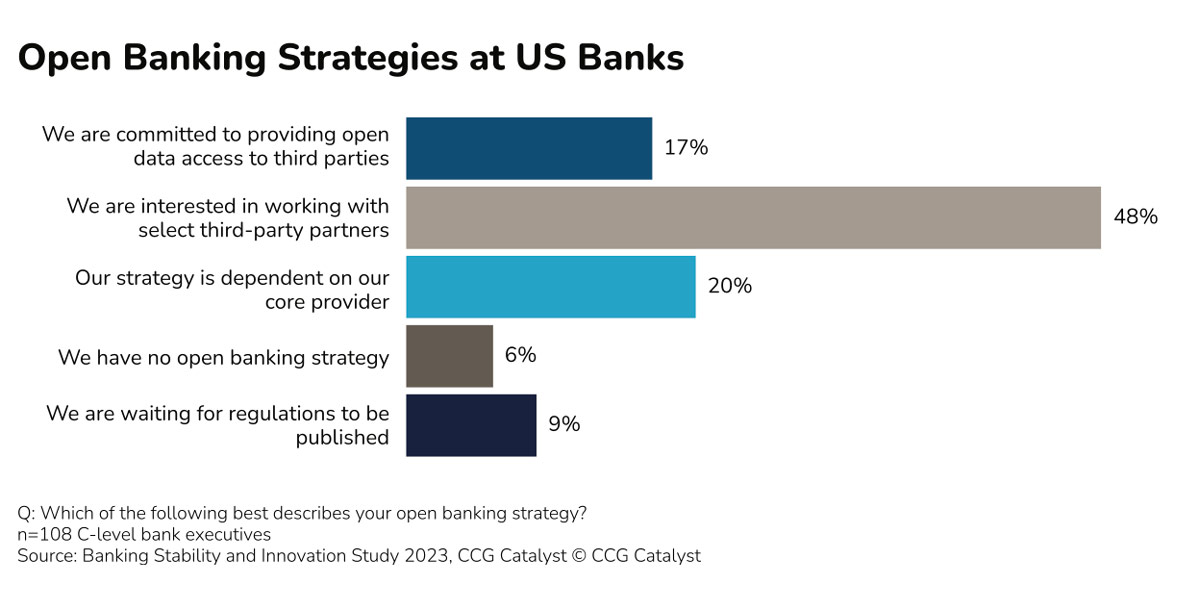

This move has implications for how consumers access their financial data and what they might use it for, and it in effect opens consumer data up to an ecosystem of fintechs and nonfinancial companies. But it also creates compliance challenges for FIs, which would be required to provide data they may not want to or in a way that requires infrastructure, likely including application programming interfaces (APIs), they might not have. According to CCG Catalyst’s Banking Stability and Innovation Study 2023, only 17% of US bank executives surveyed are committed to providing open data access to third parties.

Part of the problem is that, until now, API-based data-sharing has been a choice. Demand for fintechs’ products over the past decade pushed FIs and vendors to build APIs for securely connecting account data to fintechs that use it to provide services. Today, the largest FIs offer developer centers that include APIs for consumer data-sharing567 guided by principles laid out by the CFPB in 2017 as part of its process.8 But others are dragging their feet. FIs are bound to have asked themselves questions like, “What if sharing data just helps fintechs compete for my customers?” or “Is this a security breach waiting to happen?” or “Can I get my tech stack to handle this?”

Meanwhile, in the absence of regulation, aggregation services emerged, providing fintech apps with the infrastructure to scrape customers’ data from FIs through shared login credentials. In that sense, FIs haven’t had a choice about giving up consumer data. But the use of this practice, called screen scraping, is a far cry from open banking and has made the customer experience and data security suboptimal. (Some of these providers have since begun to connect to banks directly via API, but that is a piecemeal effort still very much in progress.)

Going forward, the CFPB’s rule could change the game, but the industry will need to contend with all that’s happened in the time it’s taken to emerge.

How we got here

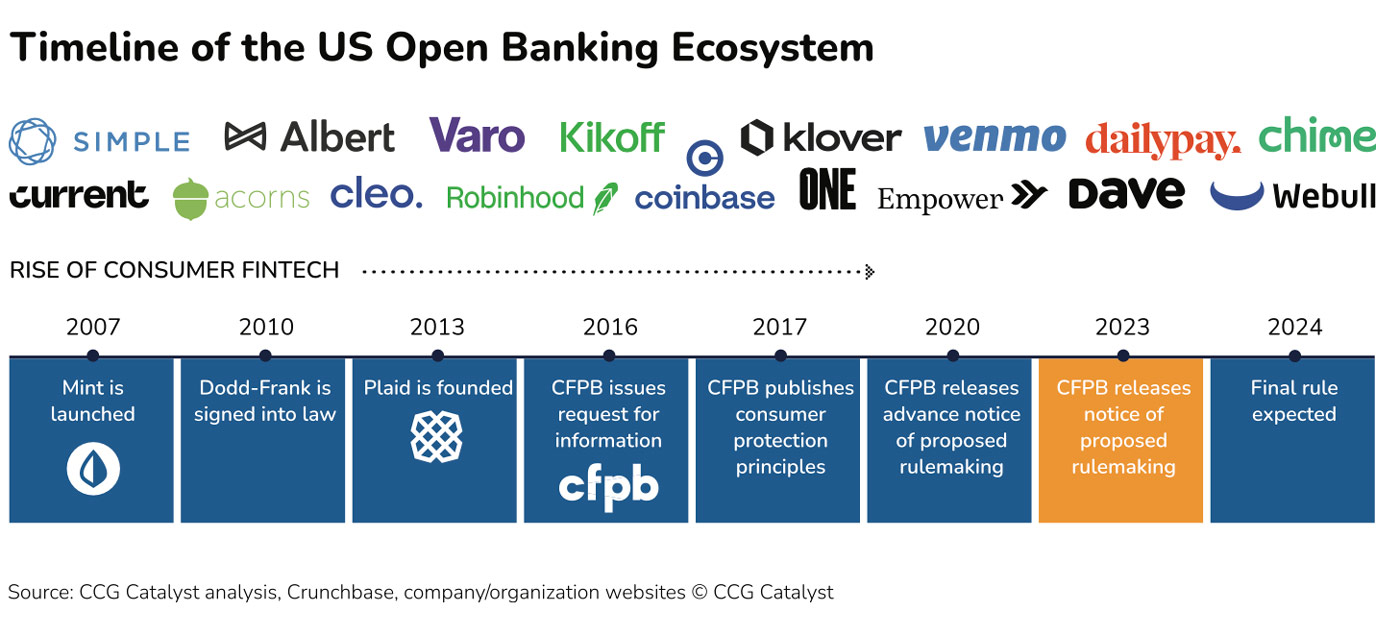

Early consumer-permissioned data-sharing, the precursor to open banking, developed in the mid-2000s with the popularity of web-based account aggregators like Yodlee.9 Early personal financial management (PFM) player Mint pulled consumers’ banking data from multiple FIs using a Yodlee connection, combined the data into a ledger, and layered budgeting tools on top while keeping balance and transaction data up to date.10 With Mint, the idea that consumers could use their banking data within a third-party app became normal. The practice of scraping account data from secure websites did, too. But the number of fintech apps on the market looked nothing like today’s.

Then two things happened:

- The consumer fintech industry lifted off. In 2009, the first neobank in the US, Simple, was launched.11 Over the next five years, countless consumer fintechs were founded across the country. The ecosystem grew rapidly with additional neobanks, personal finance tools, investment apps, and payment apps.

- In 2010, the Consumer Financial Protection Act was signed into law.12 It included a passage that mandated the electronic release of consumers’ financial data upon their request.13 This provided the fintech industry with legal cover to pull data from consumers’ bank accounts, though no guidelines around how were yet implemented.

It would take another decade or so for the CFPB’s proposed rule to emerge, but these elements combined were enough to drive an industry-led march toward open banking. Plaid, today’s biggest name in open banking infrastructure, was founded in 2013,14 and with it came a widespread movement to connect fintech apps to bank data either through APIs providing access to many banks at once through scraping or via direct agreements with individual FIs.

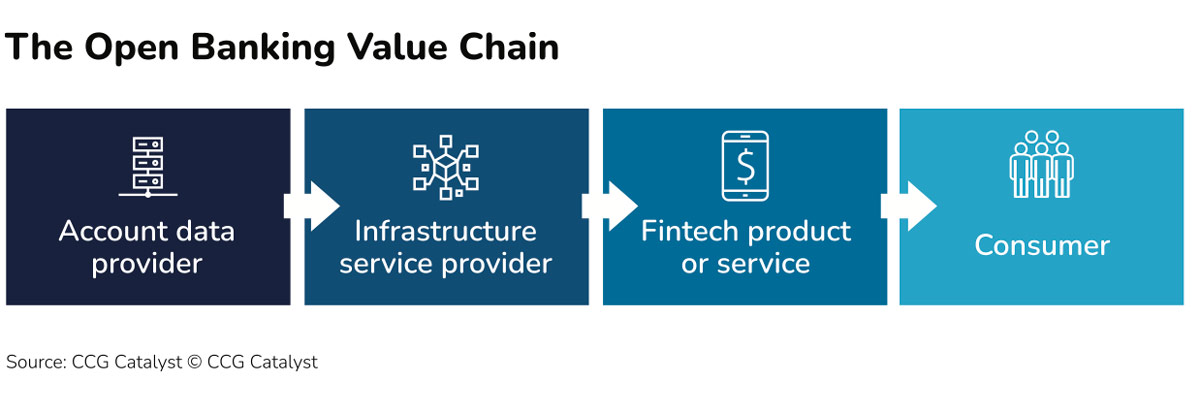

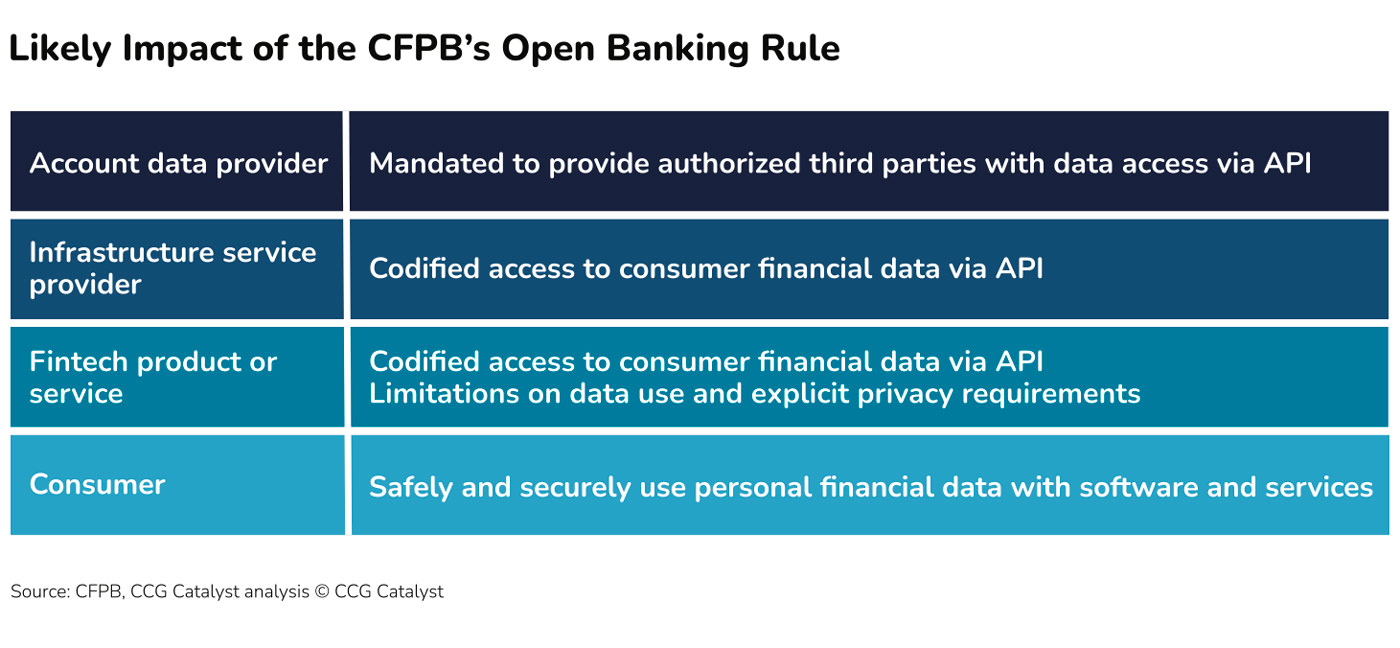

With that infrastructure in place, a de facto open banking framework emerged with three parts:

- The consumer account data held by FIs, which provide it (either knowingly or not) to fintechs that use it to feed products and services for their customers.

- Infrastructure service providers like aggregators, which provide APIs to fintechs and retrieve information from a consumer’s bank accounts on their behalf.

- Apps or platforms that use the data to provide a product or service to the consumer. These apps have often been consumer fintechs that use bank account information to verify account and routing information to fund accounts, perform know-your-customer (KYC) processes, and to import data PFM tools use.15

This de facto framework embodies the state of open banking in the US today. It is almost entirely defined by industry players, with FIs taking as active or as passive a role as they like.

Moving toward regulation

As banking and fintech worked out a de facto open banking system, regulatory efforts directed by Dodd-Frank plodded along.16 The CFPB got started 6 years after the law was passed with a request for information from industry stakeholders (FIs, aggregators, other fintechs, and trade groups).17 One of the results of that feedback was a list of “consumer protection principles,” which ultimately formed the philosophical basis for the CFPB’s rulemaking process.18 It finally released proposed regulation for open banking in October of last year.

Implications of the rule

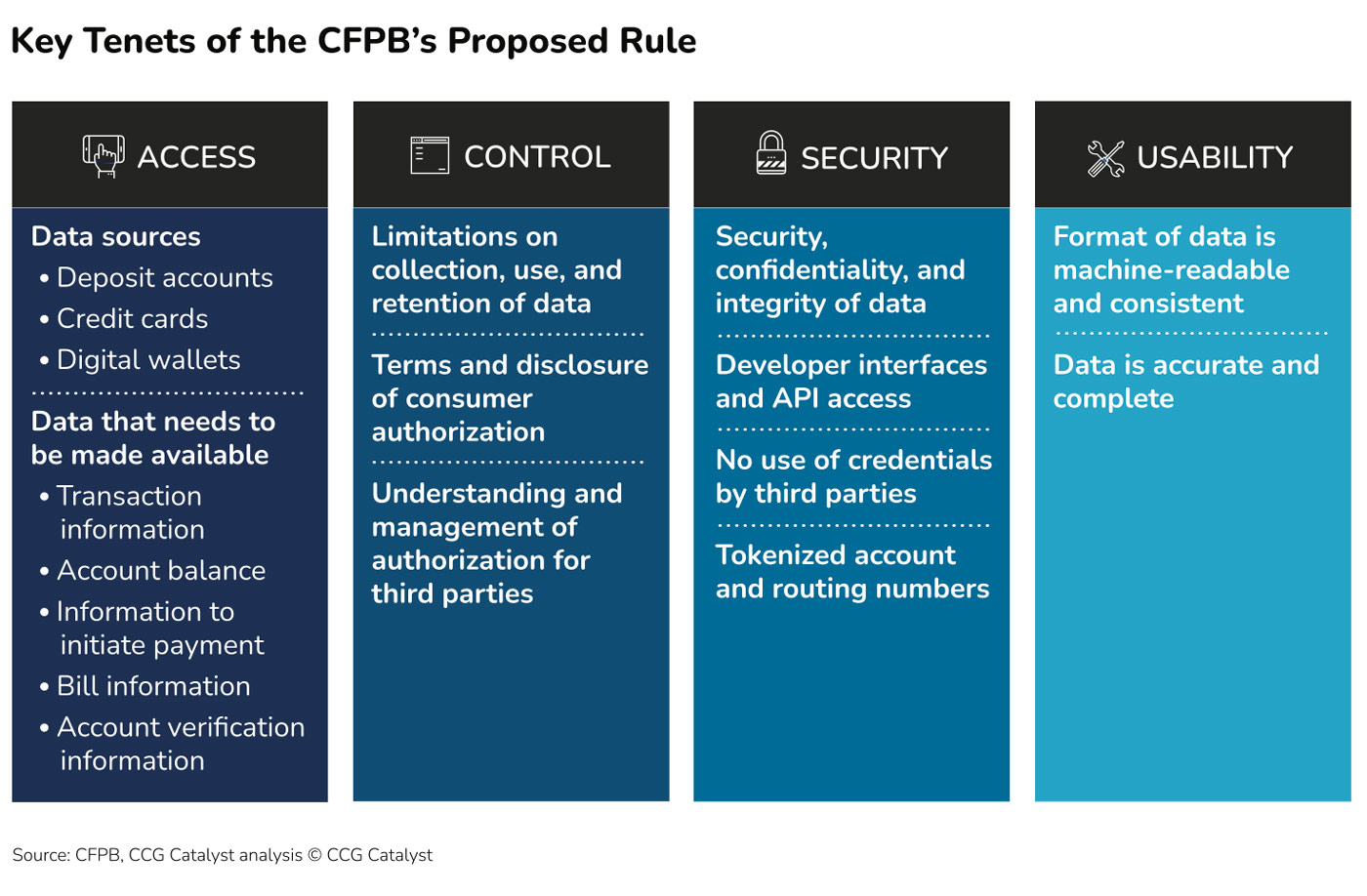

Those principles fall roughly into four buckets: access, control, security, and data usability: That consumers are able to get their hands on information associated with the financial products and services they own; understand and control which companies are using that information; know that their information is securely accessed, stored, and distributed; and that the data is accurate, complete, and provided in a usable format. Based on these principles, the CFPB’s proposed rule explicitly states the scope of data third parties can access, the terms of access for that data, and the mechanics for accessing that data. From the CFPB’s perspective, it is designed to help consumers protect the use of their financial data and resolve friction between FIs and fintechs.

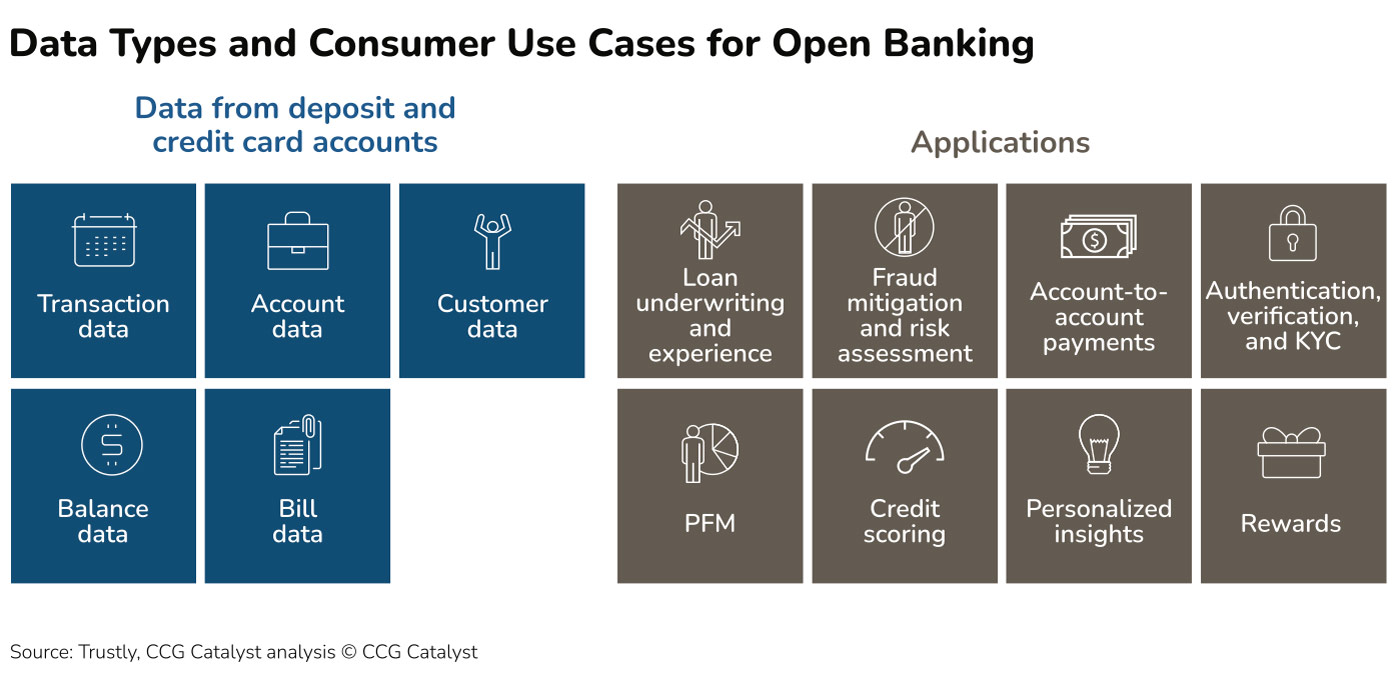

According to public comments and outreach cited by the CFPB, there is now broad consensus that API-based interfaces should supplant screen scraping in how consumers’ financial data is shared. But different players’ interests and motivations don’t always match up. There has been disagreement about the amount of data that FIs should share, data security, risk management, consumer privacy, and liability. If the CFPB’s rule goes into effect as written, it will enforce open banking for checking, savings, and credit card accounts, prepaid cards, and digital wallets; require APIs and a developer interface; effectively ban screen scraping and credential sharing; and clarify the data that a bank must make available.19 This has broad implications for the open banking framework the industry operates under today.

Practical considerations for FIs

The most work following implementation of the CFPB’s rule would likely fall on FIs. After all, they’re the custodians of the data in question. Ultimately, this demands two things. First is a shift in mindset to embrace open data access, and second is a commitment to infrastructure modernization. Assuming the first is a hurdle that we’ll clear in time with few practical considerations, let’s focus on the second. There are over 8,000 FIs in the US, few of which have large technology budgets and most of which rely on vendors like Fiserv, FIS, Finastra, or Jack Henry for their technology needs.20 Some large banks are already prepared.212223 But smaller FIs will likely have to wait for their core vendors to align with the CFPB’s requirements in order to comply.

Open banking APIs are on vendors’ radars. In particular, consent management, a focus of the CFPB draft rule, is expected to evolve along with the regulation in addition to data orchestration, aggregation, and data cleaning, Barbara Negron, senior director, platform partnerships at FIS, told CCG Catalyst. But this will take time. Additionally, while the proposed rule would prohibit FIs from imposing fees for establishing or maintaining the interfaces required or for receiving requests or making available covered data, it is unclear whether vendors could or would charge in some capacity to set up those services.24 And it appears FIs are worried about this — in fact, a number of smaller institutions have already expressed desire for a phased approach that would ease the technological and cost burdens of implementing open banking-related APIs.25

One way to get ahead is to think about modernization broadly. FIs are already exploring modernization to their core systems — and by extension, other major technology upgrades — for a variety of reasons. Baking in an open banking strategy to those larger plans by ensuring they include an API and orchestration layer that enables third parties to read data from the core would make future compliance efforts much easier.

What’s next

The near future of open banking is driven by more, better data from consumers’ checking, savings, credit card, prepaid card, and wallet accounts, provided the CFPB’s rule comes into play. Risk scoring and underwriting based on cash flow data, for example, or more personalized financial services have greater potential with holistic spending and saving data that can be retrieved regularly and securely through robust connections. The customer experience for account-to-account payments may improve with widespread identity verification and balance confirmation.

But the biggest near-term step forward is probably with PFM products and services. Comprehensive, up-to-date cash flow data from stable connections with every one of a consumer’s FIs could make near-real-time insights and recommendations a reality. Machine learning has foreshadowed comprehensive financial guidance, recommendations, and rewards, which has even greater potential due to custom content created by generative artificial intelligence (AI) and interactions driven by natural language processing.

Other changes will be under the hood. Beyond authentication, account verification, and KYC, open banking may improve the customer experience for loan applications with support for income verification. It may also make credit scoring more comprehensive by making it easy to report bill payments. Quickly emerging other use cases are fraud mitigation and risk assessment, which may include anti-money laundering (AML) screening and ACH risk scoring.26

What could be

Open finance

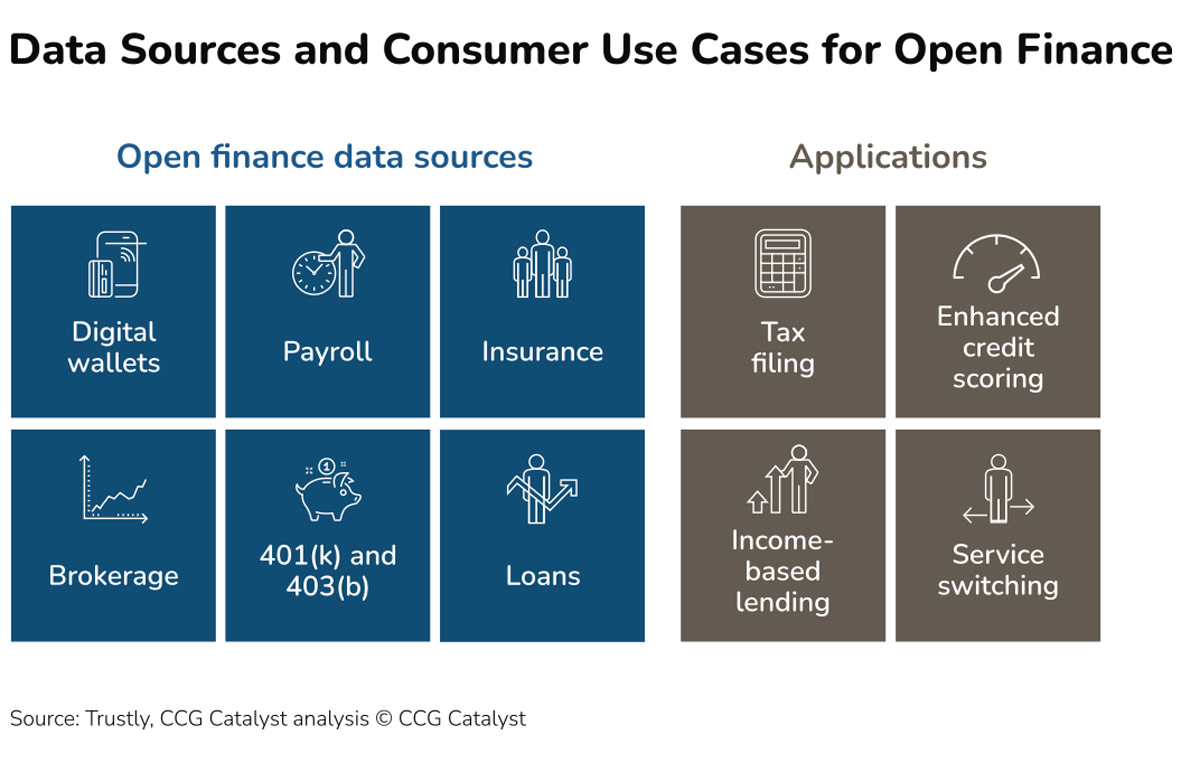

Except for a brief mention of digital wallets, the CFPB’s open banking rule passes over open finance. In other words, it kicks the can down the road for mandated API-enabled secure data-sharing for types of financial accounts beyond checking and savings, wallets, and credit or prepaid cards. Open finance use cases haven’t yet been broadly addressed by the private sector, either.

In an open finance regime, APIs could emerge for financial products like loans: Banks could provide loan principal, interest, installments due, and term of the loan. Another example might include detailed brokerage account information, like position details (number of shares, holding period, cost basis, gain/loss, and total return). Fintech apps would expand the scope of their features and new ones would enter the market. But for them, we will have to wait. As John Pitts, policy lead at Plaid, explained in an interview with CCG Catalyst, the CFPB will be watching to see how well the industry creates open finance for itself before writing additional rules.

Business accounts

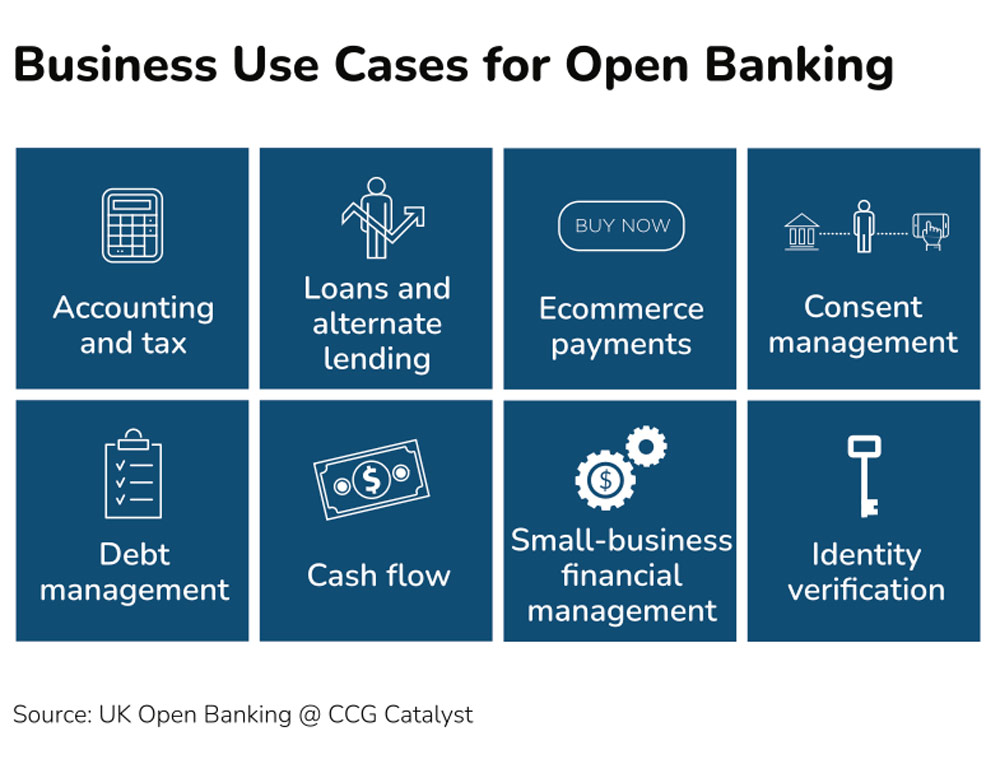

The CFPB’s proposed rule doesn’t cover business accounts, unlike open banking regulations in the UK and EU. The private sector hasn’t addressed it either. If either case came to be, it would transform business-to-business (B2B) fintech. Developments in the UK’s mature open banking market suggest how that might play out. Groups of products and services might include the eight categories of fintech tracked by UK Open Banking.

Specific examples include Iwoca, a small- to medium-sized (SMB) loan decisioning and digital lending platform27, Quickfile28, an invoicing and accounting tool; Armalytix29, software that conducts compliance checks based on information from a bank account; and Monily30, which reconciles receipts and expenses. Anna31 offers invoicing, expense management, and tax tools, and embeds a business bank account. Experian Commercial Acumen32 handles open banking-enabled commercial underwriting.

What to do today

Until late 2024, open banking will tread water. The public comment period for the upcoming open banking regulation closed in December, and the CFPB will spend until the fall finalizing it.33 In the meantime, consumer fintechs can celebrate this progress on their interests while continuing to build products that use consumer-permissioned financial data in the ways that they’ve been accustomed to. Aggregators can continue to build value-added services on top of the open banking data they process. FIs, however, need to prepare for compliance. FIs that haven’t implemented open banking APIs and developer centers need to ask how they will comply, who will they work with, and what it will cost them.

The final rule will likely vary little from what we see in the proposal, as remaining rulemaking appears to be coming down to minutiae (with many specific requests for public comment).34 Provided it is implemented, though, the breadth of the open banking ecosystem will expand dramatically, at such a time as all FIs are required to comply. The end game is an ecosystem in which consumers ultimately control their personal financial data and can share it freely and securely with products and services they wish to use.

©CCG Catalyst 2025 – All Rights Reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Read Open Banking: Is the U.S. Ready?

Download a PDF of this article