Environmental Sustainability in Banking: Rising to the Occasion

The move toward environmental sustainability in banking, particularly in the context of carbon-related initiatives, is seeing increased activity in the US and globally. Sparked by a number of drivers, including regulatory pressures and societal shifts, this push is ushering in new ways of doing business and thinking about financial services as institutions look to reduce emissions across operations and other activities. While it may be tempting to think of this shift as simply an offshoot of the climate change movement, it’s much more than that. Companies globally, both in and outside of financial services, are beginning to look at environmental sustainability as an area of opportunity. For banks, this means not only keeping stakeholders happy in an atmosphere characterized by greater focus on corporate responsibility but also the potential to reduce costs, participate in new markets, and reach more customers with additional products.

In this report, we take a look at where the environmental sustainability in banking movement is today, the drivers behind it, and what it means to participate. In particular, we explore the concept of “net zero” emissions as well as the elements of a viable impact measurement program, and profile a couple of banks already on their journeys. This is an extremely new area, and there is a lot of noise out there. The goal of this material is to cut through all of that to provide a good understanding of how banks are approaching this space and why institutions should take a closer look, even if climate concerns aren’t currently central to their overall business approaches.

What is environmental sustainability in banking and why does it matter?

Environmental sustainability refers to the concept of conserving the world’s natural resources to support the viability of the planet now and in the future. Specifically, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), it’s “about meeting today’s needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.” 1 While there are many ways the spirit of this idea could be interpreted, for most banks, it generally equates to reducing their carbon or greenhouse gas emissions, with the ultimate goal to get to net zero — defined by the United Nations as achieving as close to zero emissions as possible, with any remaining emissions re-absorbed from the atmosphere 2 — by 2050 in accordance with The Paris Agreement’s target to limit warming to 1.5 °C. 3 In the simplest terms, that means a bank adopting an environmentally sustainable approach to business will need to track, measure, and effectively manage its carbon footprint.

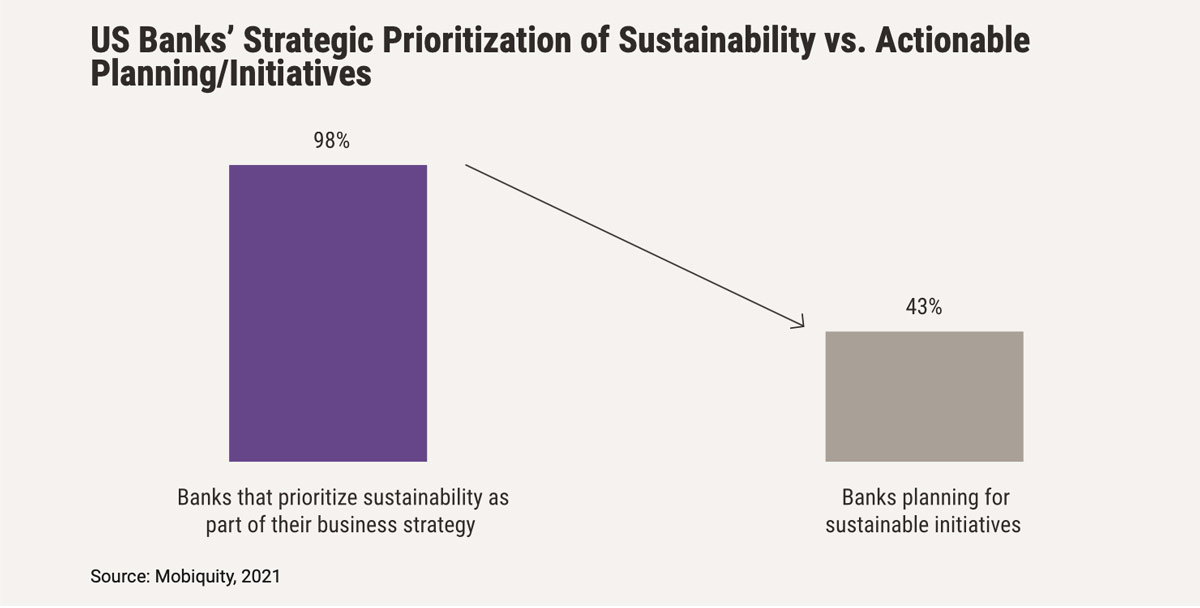

Interest in such initiatives is taking hold inside organizations across industries, and banking is no exception — in fact, according to a report by Mobiquity, 98% of US banks surveyed say they are prioritizing sustainability as part of their business strategy. This is likely in response to a number of factors, including:

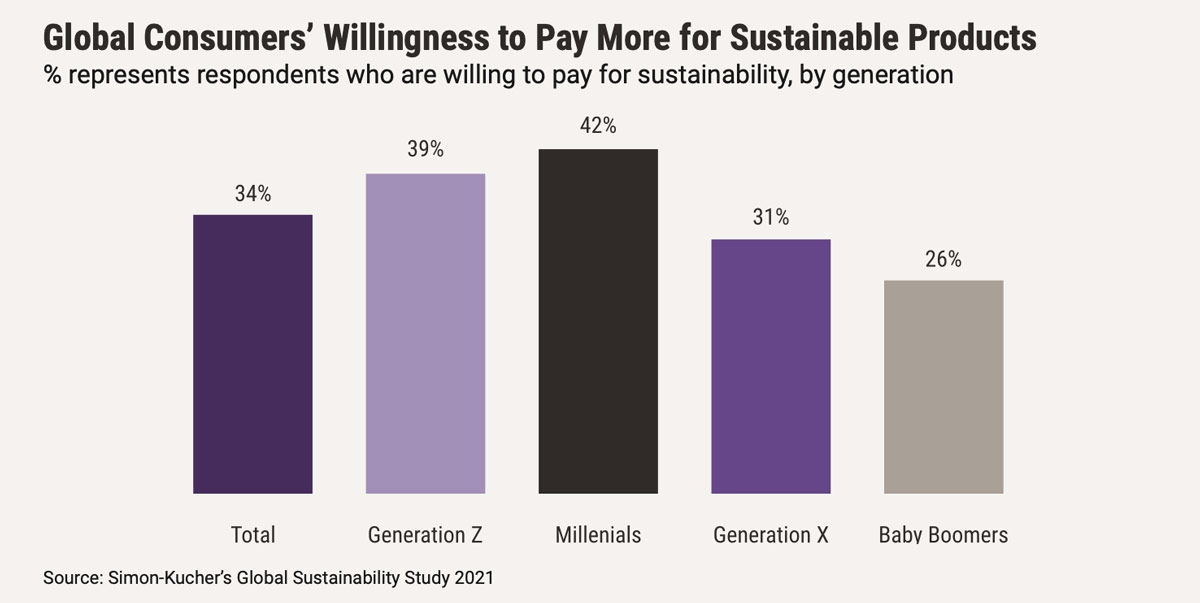

- Interest from stakeholders. Interest in environmentally sustainable business practices is growing broadly among stakeholders, including from investors looking to reduce their climate exposure 4 and customers interested in mitigating their own carbon footprints. 5 That’s pushing banking providers to adjust their outlooks and practices in an effort to keep these groups satisfied, happy, and loyal. This is perhaps the most holistic and wide-reaching driver today, with demand from a bank’s individual stakeholders likely to be a dominating factor in how it responds to the sustainability conversation. Beyond loyalty and retention, though, there is also an opportunity here to drive more business — according to Simon-Kucher’s Global Sustainability Study 2021, more than a third of consumers surveyed globally said they would pay more for sustainable products generally across categories, with Generation Z and millennials showing particular inclination. Some banking providers are leveraging this demand to open up new categories of products and services; neobank Aspiration, for example, helps users track their climate impact using transaction data and offers features like rounding up spare change that is invested in planting trees. All of the company’s products are subscription based, and it currently has over 5 million users, according to CEO Andrei Cherny.

- Regulatory pressures. An extension of the stakeholder conversation but worthy of its own is the regulatory element to all of this. While progress overall has been relatively slow in the US, we’re starting to see regulatory pressures mount with growing frequency: In March 2022, for example, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued its long-awaited proposed climate disclosure rules 6 and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) issued a proposed statement of principles for climate-related financial risk management for large financial institutions. 7 Additionally, the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act is being hailed as landmark legislation on climate in the country. 8 Given the current administration’s stated focus on this area, 9 as well as active efforts among global regulators, 10 it’s probable that regulatory activity around environmental sustainability will only continue to increase moving forward. As such, while there is always the possibility that momentum will stall or retract at some point, especially given recent uncertainty, 11 an eventual reality where climate-related programs are obligatory for banks isn’t an unlikely scenario.

New business and financial opportunities.

In addition to pressures from external forces, the global shift toward sustainability is bringing with it a reallocation of capital that will lead to new opportunities for banks. Investments in new technology in areas like green energy, for example, present a greenfield for financial institutions. These markets will grow over time, leading to entirely new industries and kinds of companies to serve through financial services. For context, in the US alone, investment in clean energy hit $105 billion in 2021, according to data compiled by Statista. 12 These companies will need somewhere to store those funds as well as additional services like access to credit. Moreover, banks that shift their own operations away from traditional energy sources have an opportunity to c ut costs internally — per the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, energy from fossil fuels costs $0.05-$0.17 per kilowatt-hour, while solar costs come in at $0.03-$0.06 per kilowatt-hour, on average. 13 This potential for better business outcomes is a less talked about driver behind climate initiatives in banking, but it’s also an important one. As banks realize that engagement on this frontier presents an opportunity for improved performance, it is taking the conversation beyond responsibility and creating yet another motivator to act, according to Sarah Kemmitt, secretariat lead at the Net-Zero Banking Alliance, one of a number of industry-led groups that seek to promote and support net zero commitments.

Business and reputational risk.

Banks also face risk from a couple of angles if they do not consider the implications of environmental sustainability. First is the business risk associated with missing out on opportunities to enter and benefit from new markets as outlined above. That could dampen future revenue and returns. In a similar vein, there may be also potential for challenges related to the failure of companies they currently loan to in planning for their own transitions away from fossil fuels, especially if a bank’s portfolio is heavily weighted toward certain industries like agriculture, manufacturing, or transportation, 14 as well as the possibility that key business lines could retract or be eliminated altogether. Additionally, as stakeholders broadly continue to embrace sustainability, there is a reputational risk component at play, as banking providers could face public perception issues if they’re not seen as adequately rising to the occasion. That, in turn, could result in damaging business consequences — in fact, according to data from Simon-Kucher, more than one-third of consumers would change banks if they felt their current one wasn’t sufficiently climate-conscious. 15

The convergence of these drivers is leading more and more banks to think about the climate discussion and how it applies to their business. At this point, there’s no doubt about that; the conversation is underway, and it’s a powerful one. However, it’s important to point out that, as an industry, we’re still working on turning that thinking into action — in fact, while nearly all executives surveyed by Mobiquity reported making sustainability a priority, just 43% are currently planning for sustainable initiatives. This data is both stark and extremely contradictory, but it’s not really all that surprising. Sustainability is an area that’s easy to talk about and harder to tackle, in large part because it requires developing ways to track and measure things that have never been tracked or measured before. As a result, although banking executives certainly seem keen to incorporate sustainability into their organizational approaches, many aren’t yet actually doing much about it. This is understandable, but given the growing incentives to engage, it’s likely unwise to dawdle much more in turning intentions into plans.

So, how do we do that? The first step is to get an understanding of what exactly you’re supposed to be measuring. What makes up your carbon footprint? How are emissions defined exactly? The answers to these questions typically come from the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol,16 which is widely recognized as the global standard for companies and other organizations that are looking to prepare a GHG emissions inventory. In short, it is the go-to source of guidance for any entity just getting started on this journey, including financial institutions. In the next section, we will explore how the GHG Protocol is designed as a framework for measuring carbon emissions, the specific implications it has for banking providers, and how its various elements can be put into practice.

The path to net zero

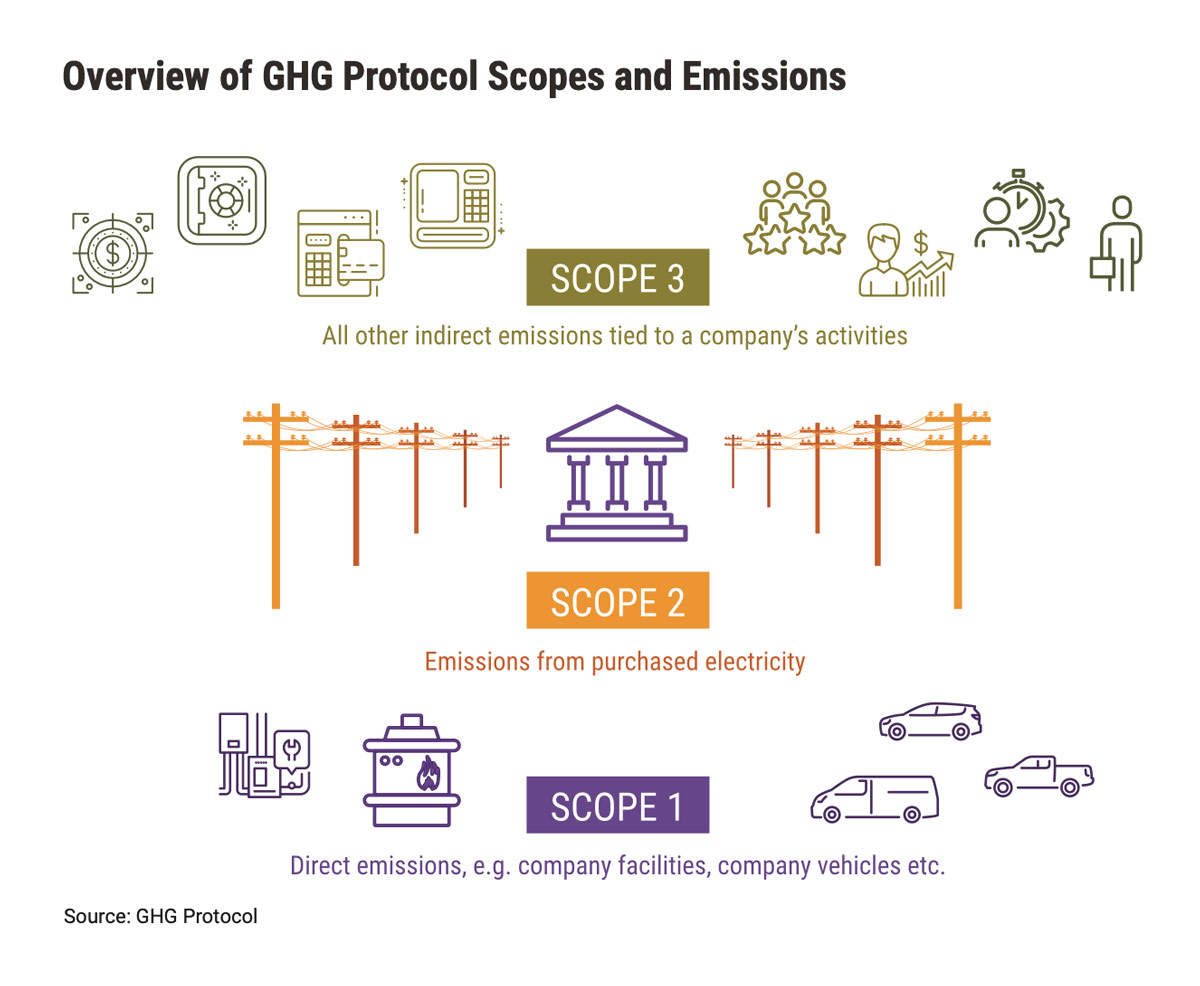

The ability to accurately measure your carbon footprint is central to any impactful sustainability strategy. Without a good understanding of your current emissions, it’s impossible to successfully implement ways to manage and reduce them. That’s why this is always the starting point. The goal of the GHG Protocol is to give organizations an understanding of what they need to measure in order to get an accurate picture of their activities in this regard. According to the GHG Protocol, emissions are measured across three distinct categories, called scopes, which include direct and indirect emissions as well as emissions related to your entire value chain.

The three scopes under the GHG Protocol are defined as follows:

- Scope 1: Emissions that come directly from sources owned or controlled by a company, such as boilers, furnaces, or vehicles.

- Scope 2: Emissions that occur from purchased electricity a company consumes.

- Scope 3: All indirect emissions outside of Scope 2 that may be a consequence of a company’s activities but occur from sources not controlled by the company.

Understanding these scopes is a good precursor to any other activities. While they do not solve the “how,” they provide a solid and accepted foundation for the “what.” Put another way, the scopes laid out by the GHG Protocol essentially serve as an ingredient list for an effective impact measurement program. The most important thing to note when looking at Scopes 1-3 is that they cover different kinds of emissions with varying difficulty when it comes to measurement. Specifically, emissions covered in Scopes 1&2, those related to your own operations, are generally more straightforward to track than those related to activities that occur outside of your own walls (Scope 3).

Below, we take a look at the different elements required to satisfy these guidelines and as well as approaches to, and strategies for, measurement:

Scopes 1&2

Scopes 1&2 are often grouped together because they refer to a business’ own operations. To accurately measure Scopes 1&2, a bank needs to collate all of its data around energy consumption from its operations, such as energy used by office buildings and the use of company cars or other vehicles. While this process is generally time-consuming, these inputs can be relatively tangible to acquire because they are tied to operational data a bank in many cases has on hand — like energy bills, for example, though the level of difficulty will vary depending on a range of factors, including the size of the institution’s footprint and nuances related to its specific operations. All of that data then needs to be translated into generated carbon emissions.

Often, a bank will work with a third-party impact measurement specialist to help in this process, especially if it is a smaller institution without a large sustainability team. Florida-based We Are Neutral, for instance, works with banking clients to collect the data necessary for these calculations and sends back a report with emission equivalents for each data point. It provides a data list of required items and leverages calculators developed internally that use different coefficients based on available external data to determine a bank’s footprint. For example, it uses data provided by utility companies to translate energy usage into carbon emissions, explained Grace Ebner, accounts manager at We Are Neutral. National or regional averages can also be used in such calculations, depending on what’s available to a bank and who it chooses to work with. Another provider we spoke with, Schneider Electric, provides a cloud-based platform, called Resource Advisor, that can ingest data either by manual input or by connecting directly to a data source like a utility provider. The platform handles all of the necessary calculations and provides dashboard reporting that enables clients to track their emissions in real time, according to Cristy House, senior manager, sustainability business at Schneider Electric.

Once a bank pulls together its data and translates that data into a carbon footprint, it can begin to adjust for those emissions. That can come through initiatives like buying from a green electricity provider, insulating buildings, and/or electrifying heating etc. It can also come from carbon offsets, which are essentially a way to pay to reduce your footprint by investing in certain initiatives — for instance, a bank might invest in a reforestation project or the building of a solar power plant.17 According to Kemmitt at the Net-Zero Banking Alliance, abatement of emissions should be prioritized, and carbon offsets should be considered a last-resort solution that can compensate for emissions while a bank builds out a plan to reduce its actual footprint through the actions outlined above. Third-party impact measurement specialists like We Are Neutral and Schneider Electric work with banks to leverage offsets in the short term and build out roadmaps with specific reduction targets for the longer term. According to Ebner, a bank that is a member of a group like the Net-Zero Banking Alliance will usually be expected to calculate its emissions for Scopes 1&2 in the first year and to begin setting reduction targets and plans for those emissions after that.

Scope 3

Scope 3 is technically considered an optional reporting class, but it’s becoming a critical component 18 of impact measurement, with most experts agreeing that it is impossible to accurately calculate your carbon footprint without it. That is true across industries, but, in banking, Scope 3 is particularly important due to the last of its 15 categories, which refers to investments. Scope 3, Category 15 emissions include those related to equity investments, debt investments, project finance, and managed investments and client services, and they are estimated to be 700 times greater than direct emissions for financial institutions, according to a 2021 CDP report. 19 That means being able to measure these emissions, often called financed emissions, is critical for banks looking to manage their carbon footprint. In fact, according to Kemmitt, this is where the Net-Zero Banking Alliance puts most of its emphasis and support: “There isn’t that much attention put on banks’ operational [Scope 1&2] emissions because they are not that significant. They have to do it, but it’s not a huge focus for us. The target setting that’s most important is around financed emissions because, for banks, that’s where most of their impact comes from.” Unfortunately, as mentioned earlier, because of the peripheral nature of these emissions, they are also the hardest to track.

The most basic way to think about financed emissions is as the portion of your clients’ emissions that are attributed to the bank across your entire portfolio. That’s why this is so hard — it requires a bank to determine its clients’ emissions and then to calculate its owned share of those emissions. According to Jorge Martínez-Blat, communications, climate policy, and technical assistance lead at Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF), which provides a detailed standard and methodology for measuring financed emissions reviewed by and in conformance with the GHG Protocol, a bank’s attributed share of a client’s emissions is equal to the percentage it owns of total financing or valuation. For example, if a bank gives a $10,000 loan to a company with total equity plus debt of $100,000, it is responsible for 10% of that company’s total emissions. While that part might be fairly straightforward, however, calculating the company’s total emissions often will not be. Banking institutions can use standards like PCAF’s to aid in this feat — PCAF, for example, provides guidelines for such calculations across six asset classes, including listed equity and corporate bonds, business loans and unlisted equity, project finance, commercial real estate, mortgages, and motor vehicle loans.

The PCAF Standard is gaining wide acceptance by the banking industry a framework for measuring Scope 3, Category 15 emissions, according to experts and banks we spoke with. To start, it provides a list of data points for each asset class that a financial institution needs to collect to measure the emissions of its clients.

- These data points can vary in quality, depending on what’s available — for example, when calculating financed emissions for a mortgage loan, the standard will ask first for actual building energy consumption; if that’s not available, a bank might use estimated consumption based on building type, size, and location.

- The standard then offers formulas for each of the data options provided that allow a bank to calculate its owned emissions.

The goal, Martínez-Blat explained, is to start with the best possible calculation method and work your way down based on what data you do or don’t have. In cases where a bank is using estimates, PCAF provides a database of emission factors available to signatories of the initiative that are regional/sector specific. The standard includes scores for data quality on a scale of 1-5, which are designed to help institutions measure the accuracy of their calculations. Institutions can work to improve their scores over time as they build out their capabilities and acquire access to more data.

Only once a bank has successfully tackled these calculations can it begin to look at adjustments that reduce its financed emissions. At that point, it will need to examine its assessment and determine which areas of its portfolio are creating the greatest impact, according to Kemmitt. For the most part, this is an exercise is balance, shifting the portfolio away from sectors or investments that are driving your footprint up and toward investments that will help bring your business closer to net zero. Banks will typically set targets for different sectors across their portfolio along the 2050 timeline and emphasize near-term action through intermediate targets for 2030 or sooner, per Kemmitt.

Scope 3 is a major challenge for institutions, even with the tools available — there’s no doubt about that. Third-party specialists can help here, as well, especially at the calculation stage, but the data collection piece is always going to be a big hurdle. As a result, institutions generally start with Scopes 1&2 and only begin to map out an approach for Scope 3 later on. According to Ebner of We Are Neutral, a bank should be looking at Scope 3 by the end of its first year in building out its impact measurement program, though it’s unlikely to begin actual calculations or target setting until year two. By then, banks should also be starting to think more holistically about their long-term roadmaps and setting reduction targets along the way. In doing so, it’s important to remember that these data collection and calculation exercises are not one and done — they need to be repeated on a regular basis, at least annually, and plans adjusted accordingly.

A note on accuracy: Given there are many different options for data usage across all three scopes, it’s worth spending a minute on accuracy. Accuracy is extremely important, but it’s also extremely hard because, the more accurate you want to be, the more data you need to acquire. For example, it’s much more accurate to measure energy output using data from utility providers than it is to use national or regional averages, but it also requires more granular information. As such, there is often a tradeoff between accuracy and ease that must be managed based on what’s available and achievable. It’s important, though, to be as exact as possible, as sacrificing accuracy can not only invite stakeholder scrutiny but also the possibility of overestimation, which could have negative business consequences.

Environmental sustainability in practice

While getting a handle on the fundamentals is important, ultimately, the best way to understand a process as new and complex as carbon footprint tracking is to look at examples of those who’ve got experience with it. As such, in this section, we highlight a few banking institutions that are already on this path and how they are working to build their roadmaps. These profiles are meant to ground our discussion in the real world and provide an overview of what it looks like to actually get started.

Amalgamated Bank

Amalgamated Bank began its work on climate initiatives back in 2016 when it committed to aligning its business and operations with The Paris Agreement. It is a founding member of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance and helped develop PCAF into a global standard by providing guidance for and supporting its North American launch in 2019. The bank published its first impact assessment, which covered Scopes 1&2 in 2017, and it began disclosing its Scope 3 emissions in 2019.

On Scopes 1&2, Amalgamated Bank works with a company called South Pole, which collects all of the necessary data from the bank and returns a report with its calculated emissions. By this point, according to Ivan Frishberg, chief sustainability officer at Amalgamated Bank, there is a pretty good system in place for pulling that data. The bank has an established data list that it developed with South Pole and uses repeatable sources internally. Today, his team is most focused on reporting for the organization’s Scope 3 emissions, especially as it relates to Category 15. The bank, which currently has $7 billion in assets, 20 began with a relatively broad approach using the PCAF standard, he explained, leveraging the data it had readily available, with the goal of improving its data quality scores over time. For example, it started out using primarily data pulled from internal systems, such as outstanding balance, location, and appraisal information for a mortgage, with some estimates like square footage based on third-party information. Now, it’s beginning to enrich that data using external sources that will improve its data quality — for example, this year, it’s working with energy consumption monitoring firm Dynamhex to access building permits and other energy data.

As of now, the bank has made no changes to its application process and does not ask clients to provide any information. While it will eventually revisit its application flow, according to Frishberg, right now, its main focus is on improving all of its internal processes to better capture and manage data. Currently, Amalgamated Bank is pulling data from different sources and putting it into a spreadsheet. That spreadsheet is maintained internally and shared with Guidehouse, another third-party impact measurement specialist, for the calculation piece. Guidehouse provides back the spreadsheet with information on emissions for each client. In the future, the bank expects to configure its systems internally to combine all of the data it’s pulling from different sources in a more automated way through its data warehouse, which will enable it to access everything at once and much more quickly.

Amalgamated Bank set its emissions targets for the first time last year, and 2022 is the first year the bank is completing its PCAF disclosure relative to those targets. It will adjust its portfolio accordingly and revisit its targets every 5 years. According to Frishberg, it’s already seeing financial benefits to its strategy, including increased credit quality and success from new product lines, particularly related to solar — 32% of the bank’s loans now come from climate solutions, and most of that is from solar lending.

Blue Ridge Bank

Blue Ridge Bank joined the Net-Zero Banking Alliance in late 2021 and is at the very beginning of building out its climate strategy to support its commitments as a member. According to Steve Farbstein, SEVP, chief revenue and development officer at Blue Ridge Bank, the bank is currently in the process of determining all of the data points it will need to collect for its first assessment. Or, put another way, it’s working to compile a data list that will satisfy its requirements for Scopes 1&2. (The bank has begun discussions on Scope 3, but they are in very early stages.)

The biggest hurdle the bank is facing currently is determining which data points to use as part of its initial assessment. Blue Ridge Bank has 26 bank branches, two operations centers, and four loan production offices, and many of those spaces were operating at reduced capacity over the last two years. In fact, a large portion of the bank’s branches were drive-thru only through a good part of 2021. Moreover, its staff went largely remote during the pandemic, and it’s unclear what kind of working model it will operate under long term. As a result, it is difficult to identify where to pull data from historically in order to create reasonable benchmarks. Before beginning to gather any data, Farbstein says the bank is focused on identifying the best way to define these necessary reference points. As of now, it is leaning toward starting with data from the second half of 2021. But, he stressed, it’s important to take the time to get it right. Notably, Blue Ridge Bank is not yet working with a third-party impact measurement specialist, which could help identify the data points needed to calculate its baseline emissions, but it may evaluate such providers in the future. The bank expects it will have a plan in place for its baseline calculations by the end of the year.

In addition to wanting to demonstrate its commitment to corporate responsibility, another driver for Blue Ridge Bank in joining the Net-Zero Banking Alliance and developing its climate strategy is the belief that regulation is coming, explained Farbstein. This is where the industry is heading, he said, adding that the bank is looking to stay ahead of any formal changes or new policies. Longer term, as Scope 3 becomes a bigger part of the conversation, Farbstein expects the bank to begin developing new products and looking at its policies around lending — for example, it could potentially encourage certain levels of energy efficiency for mortgages or homes to be built using solar. Such moves would allow the bank to build in practices that help to keep its portfolio in line with its commitments. A large part of this, Farbstein said, will be developing a communication plan for both internal and external stakeholders that explains any procedural changes and works to achieve buy-in from its staff and customers. Blue Ridge Bank’s ultimate goal is to achieve net zero by 2040 — a full decade ahead of the typically cited 2050 target.

Climate First Bank

Climate First Bank, based in Florida, opened its doors only in June 2021 and is built around environmental sustainability. It’s a full-service consumer and commercial bank but with a climate lens across all of its operations, explained Lauren Dubé, VP, director of client and mission partnerships at the bank, who oversees all of its sustainability efforts. Climate First Bank joined the Net-Zero Banking Alliance in January 2022 and is currently in the process of building out its 2050 plan.

On Scopes 1&2, the bank records data on energy output for buildings and assets it owns and sends that data to We Are Neutral, which translates it and helps the bank offset its footprint through local initiatives. It’s essentially outsourcing those parts of the process, Dubé explained, which is made easier by the fact that the bank is small and local, with only two branches. As a result, most of her team’s efforts are currently directed at how to gather all of the data needed to track and measure Scope 3. To this end, the bank is in the process of building an internal data platform that will pull necessary data points, based on the PCAF standard, together from different systems. For data it’s not acquiring currently, it is working to create a client survey that will be issued at the point of sale and ask different questions depending on what the customer is looking for. The goal is for that data to eventually flow to its internal platform where it will be combined with the data stored in existing systems. On a mortgage, for instance, square footage might come from the applicant’s loan package, while information on the building’s heating and cooling system is pulled in by the survey. The survey will be reissued to clients periodically, as needed. Once it has this system in place, the bank plans to work with We Are Neutral to calculate its owned emissions and build a roadmap with reduction targets to get to net zero.

Climate First Bank hopes to have all of the pieces in place for its internal data platform by the end of this year, with the goal of beginning to collect historical data for existing loans in early 2023. Ultimately, the bank expects to include its Scope 3 emissions with initial reduction targets in its 2022 impact report, which will be released mid-2023. Dubé noted that, because the organization is so young and adopted a climate focus from the start, the whole process is likely somewhat easier than it might be for other institutions. Climate First Bank began with a few green banking products, such as electric vehicle infrastructure loans and solar loans, and it’s slowly continued to build out its portfolio with a thoughtful lens on how it brings in new customers — for example, if someone is buying a piece of property, the bank may encourage the use of solar energy, Dubé said, adding that, especially on the commercial lending side where most of its loans originate, rate negotiation can be a very effective tactic in encouraging the adoption of sustainable practices. Because of this, its portfolio is likely already of lower impact than at many institutions. And, since it’s so newly operational, its portfolio is also still on the smaller side. In addition to its net zero commitment, the bank is working on its B Corp certification and is a member of 1% for the planet, which requires it to contribute at least 1% of its net interest margin to environmental causes.

MetaBank

MetaBank, soon to be known as Pathward, 21 is currently working on its first environmental assessment. According to Catherine McGlown, vice president, environmental, social and governance (ESG), diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), brand and communications at MetaBank, the organization is focused now on Scopes 1&2, with Scope 3 expected to come shortly after it’s completed those efforts. It’s partnered with Schneider Electric to calculate its generated emissions.

As a midsize institution with north of 200,000 square feet of owned and leased office space across Iowa and South Dakota, MetaBank has had to collect quite a lot of data for Scopes 1&2, including not only from assets it owns but also those it leases, which can be a little bit tricker if those leases include things like utilities spread across tenants and rolled up into a single figure. McGlown explained that her team spent the last 4 months working with facilities and accounting to gather all of the necessary invoices and vendor information to provide Schneider Electric with the data it needs to calculate the bank’s operational emissions. In cases where it did not have the data necessary — for example, in those instances where the bank leases buildings — McGlown and MetaBank ESG manager Kylie Brunick worked with Schneider Electric to develop assumptions in line with the GHG protocol. As of today, she said, the data-gathering process is still very manual, with the bank housing the information it’s collected largely in spreadsheets and other internal files. However, in the future, it expects to make use of Schneider Electric’s automation capabilities. In that scenario, the bank would only need to do some light auditing to ensure changes are accounted for, such as if it adds a new office space or buys a building it once leased.

By the fall of 2022, MetaBank expects to have a good understanding of its footprint across Scopes 1&2 and part of Scope 3. Once its initial assessment is complete, the bank will use the information to update and evolve its future environmental sustainability efforts. Notably, MetaBank doesn’t belong to any formal climate initiatives or alliances that would require it to meet certain environmental commitments along a timeline. It would consider joining one in the future, McGlown said, but it is currently focused on measuring its impact and determining what is best for its stakeholders. MetaBank embarked on this journey, in part, in response to feedback from stakeholders, including investors, customers, and employees, according to McGlown, though it does expect regulation to come later and is looking to be prepared for that reality, as well.

Getting started on your own journey

As the profiles above illustrate, banks are often at very different stages of progress and experiencing different challenges when it comes to their climate initiatives. That’s in part because this movement is still so new, but it’s also a direct result of the nuances in their businesses. There is a plethora of elements that can contribute to a banking institution’s unique experience here, including size, geographic footprint, operational structure, customer demographics, employee demographics, and many, many more. Given this, while there are guidelines and resources in place to provide support, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to environmental sustainability. It’s important for banks to understand this before they begin to embark on their own journeys.

If this all seems a little daunting, that’s okay. Ultimately, while the specific mechanics and processes are different for every institution, the pieces of the puzzle are the same:

- Identify the data you need to measure your baseline emissions

- Gather that data

- Calculate those emissions

- Adjust

The goal is not to build an extensive roadmap on day one, it’s simply to get moving. Among all of the experts and banking executives we spoke to, there is a single prevailing piece of advice they all share: “Just get started.” We heard it over and over again in compiling this report. If you get too caught up in the plan, you will struggle. Instead, form a small team of people who can champion the effort and task them with figuring out how to start collecting data for Scopes 1&2. Go from there. Over time, that team can build on its learnings to take on more, moving on to Scope 3 and plans for reduction.

Additionally, and of critical importance to note, any bank that is entering into this conversation will need to do it with support from executive leadership and at the board level. Everyone we talked with stressed this component — sustainability efforts do not work in a vacuum; they must permeate the entire organization, and that can only happen if it’s being driven from the top.

Urgency around environmental sustainability is growing — from demands by stakeholders to potential regulation to the business and reputational risk involved in staying on the sidelines, pressures are only going to continue to mount. This, coupled with the possibility of participating in and benefitting from new opportunities for financial institutions, is leading to an accelerated push into the mainstream for this novel arena. Once a topic tied primarily to corporate responsibility, it’s quickly becoming an area that executives are looking at for a range of business reasons. As a result, we may not be that far off from a future where every bank has some kind of impact measurement program. Those we talked with know this, and they want to be prepared. That’s what this is really about, being prepared for the future, staying ahead of the game, and capitalizing on the opportunities out there along the way. Getting prepared, though, takes time. Even those who’ve have been working on this for years are still fine-tuning their approaches. That means, for any bank contemplating their own climate initiatives, it’s probably time to get to work.

©CCG Catalyst 2025 – All Rights Reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Download a PDF of this article