Banking-as-a-Service: Navigating a New Frontier, Part II

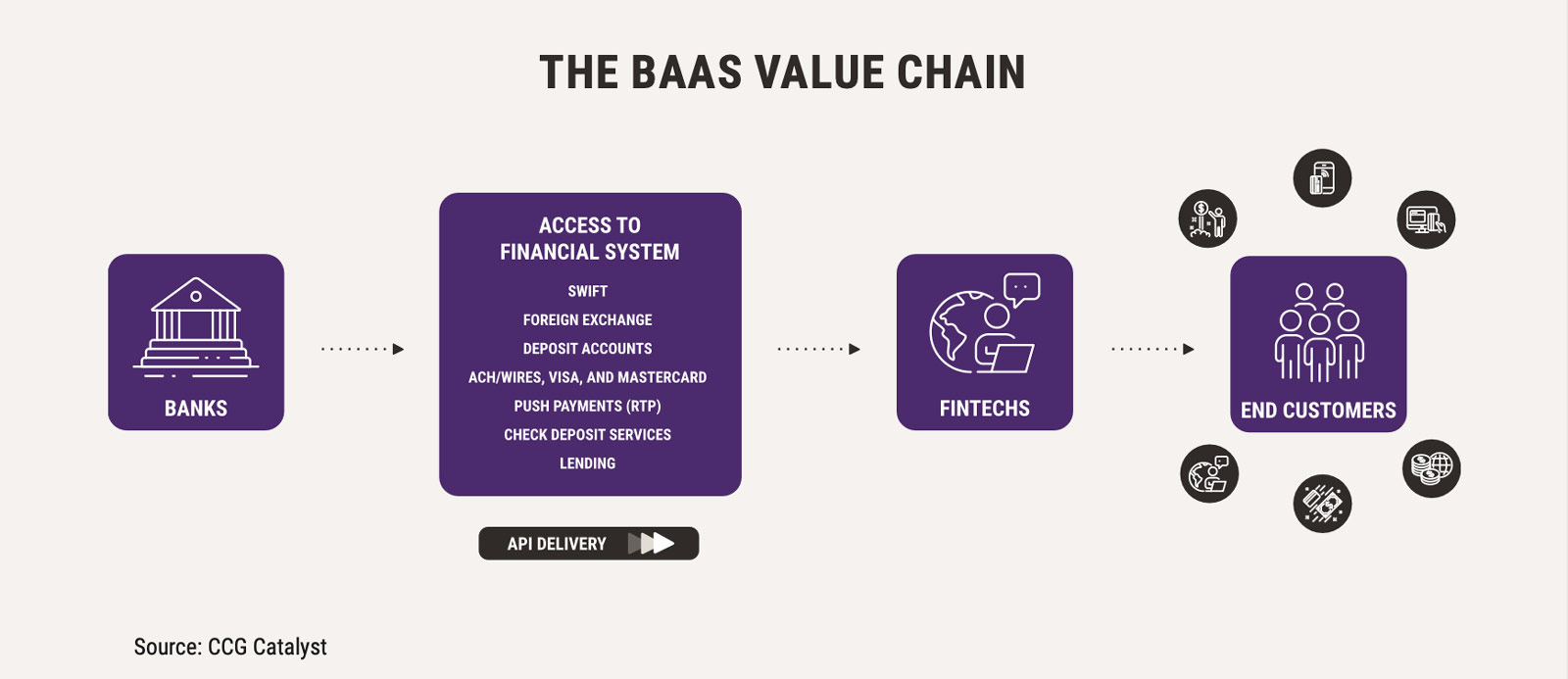

Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS) has emerged in full force over the last couple of years as fintechs and other nonbank players increasingly looked for ways to operate in the banking space without going through the grueling process of acquiring a charter. It’s effectively a way for banks to white label their regulated banking s ervices and deploy them through a third party that manages the front-end customer experience.

A BaaS business model allows a bank to outsource a two very important elements: customer acquisition and the customer experience. Both of those areas are extremely difficult to do well in an environment that’s highly competitive and driving rapidly toward a digitally advanced future. However, much of the hype around BaaS at the moment focuses on what it means for brands and how it easy it will be in the future for “anyone to become a bank.” In part one of this report, 1 we took a look at what the BaaS model looks like from the bank perspective overall and how an emerging crop of BaaS vendors is setting the standard for this new way of distribution. In this second installment, we will focus on banks that have decided to go direct, building their own BaaS platforms.

Banks that go direct manage their own BaaS relationships and operations in-house, rather than using a BaaS provider. This route gives banks greater control over their ecosystem but also requires considerable resources. Examples of institutions that have taken a direct route are BBVA and Green Dot, as well as Avidia Bank, Cross River Bank, and Metropolitan Commercial Bank, which are profiled in this report.

What is BaaS — and why is it so hot, right now?

BaaS is a distribution model by which regulated banks deploy their products through nonbank brands, effectively licensing their charters. Under this scenario, the bank partner provides regulated infrastructure to a brand, often a fintech, looking to offer financial products, and, in turn, gains access to new revenue streams. Banking products provided by some of the biggest fintechs in the country are powered by bank partners: Unicorn neobank Chime, for example, is backed by a few partners including The Bancorp Bank and Stride Bank, while digital wealth manager Acorns offers a debit card powered by Lincoln Savings Bank. This allows these fintechs to provide Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)-insured accounts to their customers. In practice, this has generally amounted to a large For Benefit Of (FBO) account in the name of the fintech, with customer accounts held as sub-accounts underneath, though the market is now beginning to embrace full demand deposit accounts (DDAs). In addition, banks are providing other products like card issuing, payments, and lending via BaaS.

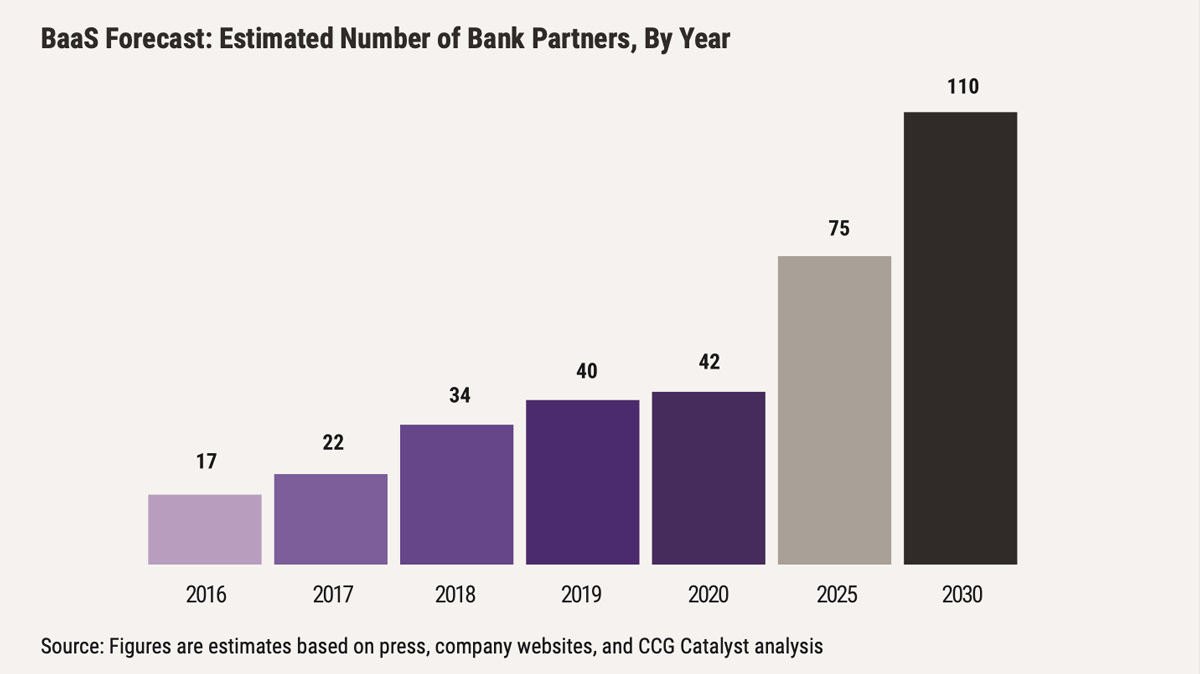

The popularity of BaaS is tied to its promise to handsomely benefit parties across the financial services spectrum: traditional banking institutions, the producers; fintechs or brands, the distributors; and customers, the users. Nonchartered brands that want to move into financial services often have the customer experience nailed but need a license to get to market; banks may struggle on customer experience but have the license and compliance expertise. Marrying these two together gives customers the experiences they are looking for under a regulatory umbrella. This synergy is putting BaaS in the spotlight and leading to deal announcements almost daily. Meanwhile, the number of partner banks has increased dramatically over the last few years, jumping from 16 in 2016 to over 40 in 2020, according to data compiled by CCG Catalyst. And that’s likely going to continue to climb as more banking institutions wake up to the opportunity BaaS presents: Partner banks tend to operate at return on equity (ROE) and return on asset (ROA) levels that are two to three times above average, per Andreesen Horowitz data. 2 However, it’s likely those banks that enter this market early that will reap the most gains and benefit from the most favorable agreement terms. That means it’s important to have a strategy today, for the future.

A key benefit to banks is in the lower customer acquisition costs the BaaS model provides. BankMobile, the Customers Bank subsidiary behind T-Mobile MONEY, boasts customer acquisition costs as low as $10 per new account, 3 compared with an industry average of about $300, 4 for example. Additionally, banks with under $10 billion in assets are exempt from the Durbin Amendment, which means they are not subject to a cap on interchange fees and can therefore build their BaaS models around transactions. As a result, BaaS is especially popular with banks that fit this bill. We’re also seeing additional revenue models emerge, including pay-as-you-go and subscription options.

While the opportunity here is quite clear, there are a number of considerations that need to be worked through in order to implement BaaS well, especially when employing a direct model. Many early BaaS tie-ups were direct agreements that came with technological and operational hurdles. Banks today can learn lessons from those partnerships and avoid some of the pitfalls that plagued first-movers in this space, while also building on those foundations. In this report, we attempt to shed light on those lessons and share best practices for banks just beginning to explore this area.

Tackling BaaS: the direct route

Tackling BaaS without help is a mammoth undertaking. It means navigating compliance and operational hurdles on your own, as well as ensuring that your infrastructure is prepared to handle not only the integrations necessary to run a BaaS operation but also the high volumes of activity that come with it. Based on discussions with industry experts and banks that have successfully chartered these waters, we have distilled three key areas that those looking to build their own BaaS platforms need to consider.

Strategy and planning

BaaS is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. Determining which products you want to offer through third-party channels, and what you want out of it will be key. For example, if an organization is looking to attract more deposits, they will come at the market from an entirely different angle compared with those looking to power lending platforms.

On the deposit side, in particular, there are a couple of options for how to structure the bank’s relationships with those who will provide the front end to consumers. This is extremely important because these different options have very different implications for the bank that span across operations, compliance, and the business model.

There are three main routes a bank can take when helping a client launch accounts:

The FBO model. The FBO model is the most common BaaS model out there today. Under this model, the bank isn’t opening customer accounts directly on its core. Instead, it opens a single FBO account in the fintech’s (or other brand’s) name. That account holds pooled funds from all of the accounts of the nonbank client’s end customers. This option has a couple of key benefits. First, it is generally cheaper for the bank to open an FBO than many individual accounts, a consideration especially for clients with low average deposit sizes. Additionally, the technological burden is much lower, as the bank does not need to be able to facilitate access to core capabilities like account opening. However, the difficulty with this approach is that it requires a huge lift on reconciliation. All of the transactions under the FBO need to be reconciled for each client. This can be a cumbersome process, and failing to do it properly has compliance implications. Additionally, because the bank is not originating individual accounts, it doesn’t hold a direct relationship with the end customers; the client relationship pertains to the third party it is banking under the BaaS agreement.

Full DDAs. Banks that offer full DDA accounts through their clients are opening individual accounts for end customers. This means that, instead of having one client account for each fintech or other brand sitting on the core, it has many accounts that are ultimately being serviced by a third party. As a result, the bank can offer a more complete BaaS proposition to the market, as it takes on the account opening and core processing elements. It also owns the customer accounts in this scenario, while, as mentioned, on an FBO model, the third-party provider maintains control over those relationships. This approach requires the bank to invest more in its technology infrastructure (see below), as it must be able to provide its clients with easily consumable APIs to perform necessary functions. However, it does alleviate the reconciliation burden associated with the FBO model.

A Hybrid Approach. Some banks we talked to offer both models. These banks tend to be those that have been around the BaaS market for a long time and want to provide options for their clients. For example, some clients may prefer an FBO approach because it ultimately allows for more control over the customer relationship, while others may be looking for a more pureplay BaaS option that equips end customers with individual accounts titled in their names. For those looking to compete in different areas and pull in different kinds of clients, a hybrid model can make a lot of sense.

Regardless of which path you end up taking, most experts say that getting the right team in place first to do the leg work on these strategic decisions is key. That dedicated team can then serve as the main point of contact down the line on the bank side of the house, ultimately owning the BaaS business and all of the relationships underneath it.

Technology and infrastructure

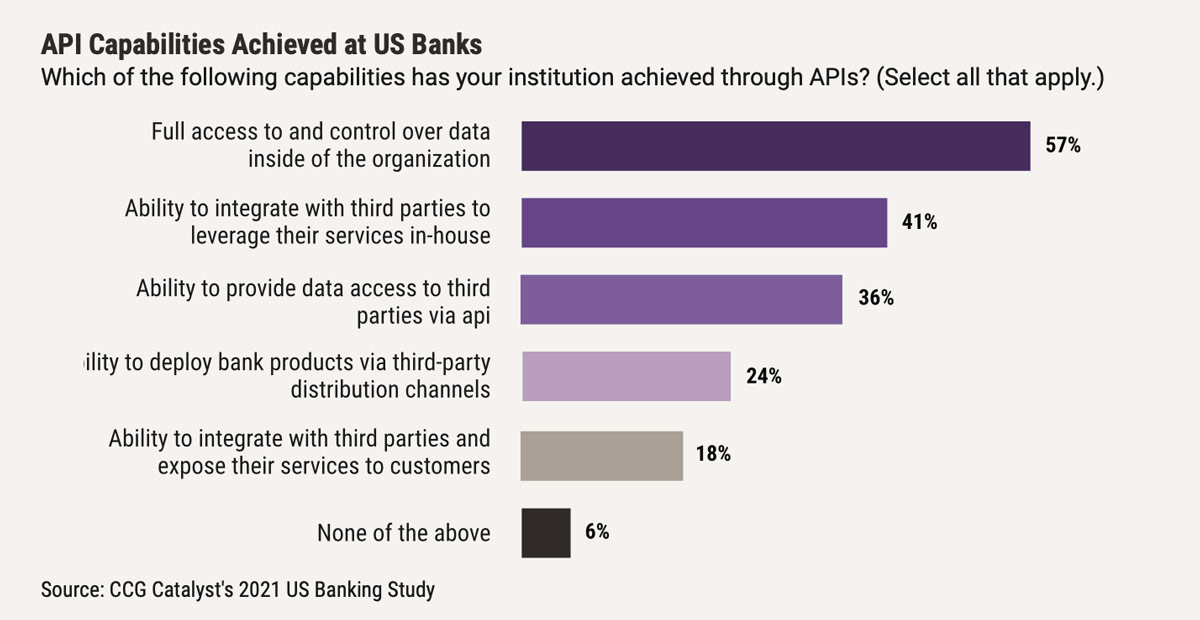

It’s impossible to do BaaS without the ability to integrate with third parties. As we discussed in our recent report, Open Banking | Is the U.S. Ready?, 5 that typically relies on the ability to deliver data and functionality through application programming interfaces (APIs). In direct BaaS setups, this is extremely important, as partner banks need to be able to give fintechs and/or other nonbank clients access to the necessary systems and functions required to power their products and services.

As mentioned, the biggest technology lift will be on banks that want to provide full DDAs. That’s because, in order to equip a third party with the ability to open and manage individual accounts, the bank needs to enable a whole host of capabilities, including account opening, inquiries, transfers, and access to account data, among other things. That requires the bank to take a truly API-first approach to its infrastructure, ensuring that its clients can easily access any function they might need. This, of course, is much easier said than done, largely because many institutions are on older core systems that weren’t built with ease of integration in mind.

Most institutions we talked to are getting around this by exposing APIs via their core system provider and then building an API layer on top to improve useability for clients. Additionally, while the technological burden is lower for those leveraging an FBO model, as there are fewer integration points to consider, it isn’t nonexistent. The bank will still need to provide access to certain systems — for example, to give clients the ability to track balances through online banking. As a result, having some sort of API strategy is an absolute must when building a BaaS unit, regardless of your approach.

Companies that provide technology that can be used to build an API or service orchestration layer in-house include MuleSoft, IBM, and Boomi. Additionally, open platform providers like Mambu and Technisys allow banks to implement these capabilities via a managed service.

Policies, procedures, and risk

There’s no area more important to doing BaaS well than compliance. Every single bank we talked to put this at the top of the list, not only because they need to be sure to stay on the right side of regulators but also because compliance is part of the service they provide to clients. Fintechs and other nonbank clients rely on their bank partners to bring their compliance expertise to the relationship; it’s an important part of the deal.

Doing this well requires building an oversight function to manage third-party relationships, starting with due diligence and pulling all the way through to ongoing oversight. This generally requires allocating dedicated compliance resources to the BaaS operation that are either embedded in or work closely with the team running the unit. The banks we talked to have very stringent processes for how they determine which clients to take on, in some cases, even rising to the level of conducting the same or similar assessments as they would for a critical vendor. Ongoing oversight typically pertains to monitoring reporting, marketing materials, as well as regular business reviews and audits, sometimes by an outside party.

Additionally, before entering into any relationship, a bank should consider mapping out all of the policies and procedures that will govern its agreements. For example, it might lay out how customers will be onboarded, know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money-laundering (AML) standards, as well as how reconciliation and reporting will be handled. While not all banks formalize their procedures this way, getting this right early can help to streamline the process down the line, ensuring the same set of guidelines for every third-party client, and making oversight much easier.

Lessons and successes from the field

There’s perhaps no better way to understand how to do something than to see it in practice. To ground this report in real-world examples, we decided to highlight a few banks that have built their own BaaS operations and their experiences, successes, and challenges in entering the market. Below, we profile these institutions.

Avidia Bank

Avida Bank, a community bank based in Massachusetts, is building its BaaS operation using FIS’ Code Connect platform. Code Connect provides a centralized API gateway and marketplace where developers and FIS partners can access FIS APIs. By leveraging Code Connect APIs, Avidia is able to provide fintechs with access to its systems to originate services. (Some services like bill pay via DirectBiller are exposed outside of Code Connect.) The bank provides access to payments services to a number of clients today, and it’s now moving into deposit accounts, with one fintech currently in a test environment and another already live. Specifically, these fintechs are leveraging a set of deposit APIs provided through Code Connect that handle origination, inquiries, transfers, access to account-level information, and other necessary functions. The bank provides DDA accounts originated directly on its core.

The process for partnering with a new fintech begins with risk and underwriting, which takes between 30 and 60 days. (The bank hopes to get that down to 10 in the future.) According to Bob Conery, COO of Avidia Bank, the bank uses the same vendor risk assessment it applies to its critical vendors like FIS to determine whether or not a fintech is an appropriate fit. “The bottom line is, we are providing banking services for individuals on behalf of another entity. That fintech needs to be no less capable of maintaining security as the bank,” he explained. Once the fintech has cleared the assessment, the bank shares general terms and conditions and begins to negotiate pricing. Avidia generates revenue in a couple of ways, including through a sponsorship fee on card products, which is basis points on dollars spent, as well as per ACH and API call fees. If the fintech is also riding the bank’s card payment processing agreement with FIS, it provides a buy rate and passes those costs through.

Most implementations are 8 weeks long and include pulling resources in from other teams at the bank, including from IT, compliance, and risk. Each fintech will come with its own technology stack, including its own ledgering system, that is approved by Avidia. From a technical standpoint, the bank’s developers work with the fintech to connect to all of the APIs that will be necessary to run its operation. Once a fintech is up and running, it is subject to an annual review, again mirroring the bank’s approach with major vendors, as well as ongoing oversight by the bank to ensure that requirements are being met in areas like AML and data security.

Avidia is a great example of a bank leveraging its existing systems and capabilities to deliver BaaS. It is, however, still very much in the process of building out its operation and plans to continue to streamline and improve its offering. In particular, Conery said, the bank is in the process of implementing an integration or API layer provided by MuleSoft that will streamline access to the bank’s systems. This will allow fintechs to connect via a single API, rather than having to integrate with many different endpoints. That’s likely to make the bank a much more attractive potential partner, especially in an environment where BaaS providers and other banks are streamlining access this way and setting a standard of service that fintech clients will come to expect.

Cross River Bank

Cross River Bank is one of the most well-known BaaS operators today, and it was also one of the earliest movers in this space. The New Jersey-based bank entered the market in 2010 on the lending side. It began by funding loans that marketplace lenders were making in the wake of the financial crisis and eventually moved into wires/ACH, and then, deposits. The evolution from a product standpoint was driven by its existing relationships and how it could better serve the needs of its BaaS clients, which today include big names like Affirm and Coinbase, explained Jesse Honigberg, SVP, technology chief of staff at Cross River Bank. Currently, the bank offers lending, payments, and FBO and DDA accounts through its BaaS portfolio. It focuses on fintech and enterprise clients that can meet its stringent compliance requirements.

The cornerstone of the bank’s BaaS operation today is its COS deposit core. It began development on COS in 2018 after it became clear that it would be difficult to scale its BaaS operation on its existing core system. Because COS is built from scratch, everything is designed to be consumed via API and development work is much easier as the system is modular. COS is only a deposit core; the bank’s existing system still handles Cross River’s legacy business, and it uses another platform built in-house, called Arix, for lending. Cross River integrates these different modules via API — for example, Arix uses the COS API for funding. Auto reconciliation is built into the system and runs in real-time with no formal “end of day” processing needed, although it can accommodate memo posting if necessary for a specific use case. All of the data is pulled together in the company’s data warehouse for consolidated reporting. Fintechs in Cross River’s BaaS portfolio are required to run on the COS core, which means that all activity is posted in real-time to the bank’s own ledger.

On the operational side, the bank has a sales team dedicated to sourcing and bringing in fintechs as well as account teams that manage the relationships. Cross River also dedicates compliance resources to provide oversight of these relationships, including handling reporting, reviewing marketing materials, and conducting regular business reviews. For larger clients, these reviews are conducted quarterly. Currently, the bank makes money on interchange and API calls, but it sees an opportunity for new revenue models as well, including licensing its COS technology to other banks, Honigberg said. According to Andreesen Horowitz, Cross River Bank’s ROE and ROA are a little more than double the industry averages of 10.8% and 1.2%, respectively.

Building and maintaining its own BaaS platform has given Cross River quite a lot of freedom, especially when it comes to developing new offerings. However, the bank has invested considerably in technology resources to make this happen. (It currently has more than 100 developers on staff.) Additionally, Cross River now has to build ongoing development into its strategy, which is a blessing and a curse — the biggest challenge is making sure not to overshoot, Honigberg explained, to ensure development and work is really connected to a client story. This is the classic trade off; the bank gets all the freedom to innovate it needs but is responsible for its own product roadmap and must be committed to allocating the necessary capital and managing the associated risk.

Metropolitan Commercial Bank

Metropolitan Commercial Bank is another BaaS veteran. It first entered the space through its own subsidiary, called CashZone, a check cashing services provider in New York City, where the bank is based. CashZone launched a Visa debit card backed by Metropolitan Commercial Bank in 2004, essentially becoming the bank’s first BaaS client. It later sold CashZone but retained the debit card business and began bringing on additional clients in 2010. The bank primarily operates on the FBO model, though it does have a couple of clients that are opening DDA accounts directly on its core. Its BaaS operations fall under its Global Payments Group (GPG) and current clients include big-name neobanks like Revolut and Current.

Today, the bank’s fintech clients generally begin by opening up an FBO. They bring their own technology stack and vendor set, including for things like KYC as well as their choice of third-party processor, all of which must go through approval. At this point, the bank is already integrated with most processors brought to the table, like Galileo or FIS, for instance, though it will integrate with new ones on a case-by-case basis. Once the fintech is onboarded, which generally takes about 3 months, most activity goes through the third-party processor selected by the fintech, though some services are provided directly; fintechs can track balances through the bank’s online banking platform, for example. Functionality that is delivered by the bank directly is done primarily through APIs exposed through Metropolitan Commercial Bank’s core provider. To streamline and enrich this delivery, the bank is in the process of implementing an API layer using Dell’s Boomi software.

On the compliance side, Metropolitan Commercial Bank takes a three-pronged approach. The first step is the risk assessment conducted before a relationship is entered into, the second is the KYC and AML requirements placed on the fintech, and the third is ongoing oversight. According to Mark DeFazio, president and CEO at the bank, this last step is the most challenging part of the business, in large part because most of the activity doesn’t flow through the bank’s core. As a result, every day the bank needs to collect reports from many different processors and reconcile all of the transactions that occurred outside of the bank’s environment. To make this process easier, the bank has put systems in place over time that integrate the data needed for reconciliation and deliver reports. There is a dedicated group that is charged with reconciling using those reports. In the future, the bank plans to implement a real-time dashboard powered by an integrated data warehouse that everyone can see.

Compliance is by far the most important aspect to Metropolitan Commercial Bank when it comes to its BaaS operations. In addition to its three-pronged risk management approach, the bank also embeds compliance resources throughout the BaaS business in areas like legal and operations. And each fintech is subject to an annual third-party audit. As DeFazio described it, the bank has had to build (and is still building) an enterprise-wide compliance management function for third-party oversight. “Regulators can’t walk into Revolut, so they come in this door,” he said. “This is where the rubber hits the road in responsibility and liability.” In another year or so, DeFazio expects there to be more technology on hand to help. In fact, it’s already starting to emerge — for instance, a major challenge for the bank has been monitoring changes to terms and conditions on the websites of its clients to ensure they are up to date with the latest regulation, and recently it’s been able to improve that oversight by implementing web crawlers that scan for changes and automate the process.

Metropolitan Commercial Bank’s investment in providing not only access to the financial system but also in delivering compliance and operational support in a repeatable way has paid off in its client list. It currently supports dozens of programs and is focused now on how it can scale operationally as it adds more and more customers, especially as some of its clients begin to hit user numbers in the millions — Current, for example, boasts 2 million customers today. 6 The bank takes a flexible approach on economics, depending on the client. Usually, it charges transaction fees combined with a deposit minimum and sometimes monthly administrative fees are included, as well.

Where we go from here

BaaS is an extremely popular topic today, and for good reason — many banks are struggling to provide customer experiences that people now expect, and it offers a way to offload that piece to a third party while still collecting not only deposits but also fees and other revenue. How to do BaaS, though, and how to do it well are really hard for most bankers to wrap their heads around. That’s largely because there are so many options — direct or BaaS provider? FBO or DDA? What about lending? And any kind of BaaS setup opens the bank up to risk and potential compliance issues. That’s why taking the time to tailor the concept of BaaS to the bank is so important. For those going the direct route, this is especially important, because it’s essentially a choice to go without help in favor of control.

For any bank getting started, it’s critical to begin with what you want to do and what you’re capable of. Some BaaS providers today would be very happy to pursue an FBO model but are starting with DDAs because they haven’t figured out the reconciliation piece. Others have core infrastructure limitations that make the DDA option a nonstarter in their eyes. Moreover, BaaS may simply not be an option for some, no matter how attractive it might seem, especially if resource issues come into play or a bank simply doesn’t have the risk appetite. The point is that each bank has to weigh all of the considerations that a potential BaaS unit comes with and chart its own journey from there. As we so often say in financial services, the answer is never one-size-fits all.

©CCG Catalyst 2025 – All Rights Reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Read Banking-as-a-Service: Navigating a New Frontier

Download a PDF of this article